When examining and assessing patients it’s easy to get caught up in all of the esoteric and minute details. With the overwhelming amount objective measurements (joint mobility, AROM, PROM, MMT, DTR, etc.) and the endless list of special tests, it can be difficulty to obtain a clear clinical picture. While a full examination is necessary to prevent overlooking any possible impairments/pathologies; it is also just as important to make sure you come away with a strong simple assessment and clear clinical picture of your patient. I have found that focusing on 3 simple assessments helps to maintain clinical clarity throughout the plan of care.

3 Simple Assessments

Range of Motion

First examine the kinetic chain to find what tissues are shortened or lengthened. Then assess for which tissue structure is restricting movement (contractile tissue, joint capsule, connective tissue, fascia, neural tension). This can be achieved most of the time with attention to detail of the end-feels, positional isolation of certain structures, and/or through palpation.

There are many professionals that believe the lack of ROM is the most important aspect to consider when treating patients. Resolving the impaired ROM will correlate with resolution of other impairments. Some believe this is specifically a result of the joint mechanics, whereas other believe it is a result from multiple tissues (joints, nervous system, muscle length). Either way, this emphasis on increasing ROM is a common approach in orthopedic practice.

An increase in ROM can have 3 potential results:

1.) Increase of muscle length range (length-tension relationship)

2.) Decrease of antagonistic force/tension and restricted movement

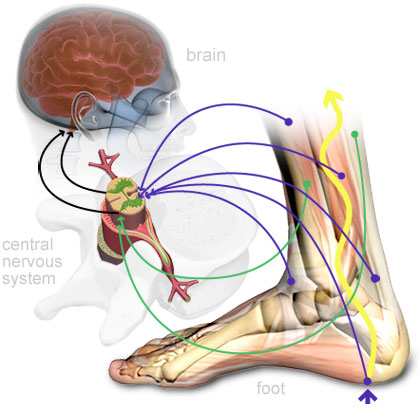

3.) Increase of stimulation of mechanoreceptors to relay information regarding body position to the CNS

Mechanoreceptors in the skin, muscle, and joints send constant information to the CNS during any change in ROM

Of course this is just the tip of the iceberg to this theory. There are a great deal of biomechanical and physiological concepts involved in fully understanding the complexity of the ROM theory. Regardless of whether you believe in this theory or not, achieving normal ROM is a necessary prerequisite to restoring normal biomechanics and functional movement.

Stability

This is an aspect of assessment that I feel alot of clinicians overlook. Having stability throughout the kinetic chain requires a great deal of muscle strength, adequate joint ROM, and sensorimotor balance. It is especially important in higher level patients that may have normal ROM and strength.

Placing a patient in a closed chain position that forces them to balance their COG over their BOS will allow for an assessment of aberrant motions and compensations. An important part of this assessment is to allow for enough time for the patient to display instability. A quick 15 second single leg stance won’t show much, but if you extend it to 45 seconds you may see all sorts of ankle pronation, femur IR, and compensated trendenlenberg.

Of course not all joints can be placed in this closed chain position for assessment. For example, you might have a lawsuit if you put a neck patient in a headstand to assess stability. So try using a combination of ROM, strength, and sensorimotor system assessment to determine your patients functional stability.

Strength

Relativity can allow for a better global assessment of strength

Einstien helped create the theory of relativity in the early 20th century that overturned Newton’s concept of uniform motion. With this new theory all motion is relative. This changed physics and brought the concept of relativity to the forefront. Of course assessing for strength is by no means quantum physics, but I think applying relativity to the musculoskeletal system has it’s place.

So what can you make one little MMT muscle strength grade relative to? I look to 3 area’s to assess for “Relative Strength”:

1) Kinetic Chain

2) Antagonist Muscle

3) Contralateral Muscle (Bilaterally)

Assessing for relative strength can often give clinicians a good idea of the integrity of an individuals musculoskeletal system and where a possible compensation is coming from. A lack of muscle strength in one area almost always leads to a compensation in another area (e.g. decreased peri-scapular strength → decreased rotator cuff strength). Keep in mind that sometimes the patient’s main complaint may be at the area of the compensation and not at the culprit of the injury.

Last but not least, don’t get caught up in worrying about + and – of MMT grades. Arguing between a 3+ and a 4- is a waste of time. It’s either weak or strong.

Bottom Line

Just an examination and diagnosis do not give a full clinical picture of a patient or allow for an individualized plan of care. An assessment is necessary for an individualized clinical picture and can lead you in the right direction for developing a unique plan of care for each patient.

Using these 3 assessments tools will give you a simplified clinical picture of your patient. In most cases addressing these 3 major impairments (ROM, Strength, Stability) will help your patients achieve optimal function.

I hope this post will remind you to take a step back and look at the simple major impairments that may be the culprit of your patients physical problems.

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.