The deep squat (aka full squat, aka ass to grass/ATG squat) is one of the most debated, talked about exercises/assessment we have in human movement. Some talk about the deep squat as if it’s the cure to cancer, some talk about it like it’s going to cause the apocalypse. I have found that I always get mixed information and many take either a full medical approach, a full evolutionary approach, or a full performance approach.

My goal here is to provide a blend of these approaches. As a PT that loves S&C and evolutionary medicine, I hope I can give some evidence, some reasoning, and some clinical judgement on the deep squat as an exercise.

Let me again emphasize this is through the lens of the deep squat as an exercise; the squat as an assessment is a whole different story (PRI, FMS, SFMA, Loaded, ADL, etc.).

If you want to stop reading here, please consider the conventional wisdom of great S&C coaches:

- Squatting is not bad for you, the way you squat is bad for you

Disclaimer

I think a big part of the discrepancy with the performance with the deep squat is that there are so many variables associated with this movement pattern. These variables include local physical impairments, movement history, exercise history, injury history, education, neuroception, structural changes, coaching, motivation, and culture.

So if you took 100 people off the street and had them deep squat, you would see a smorgasbord of different movement patterns.

This surfeit of human variables leads to a problem when trying to generalize one of the world’s most complex exercises, let alone trying to create a study.

But this abundance of variables isn’t the only problems with the studies.

3 Reasons Why Evidence isn’t the Gold Standard for the Deep Squat

- The populations vary from individuals who are young and have experience with the deep squat, to older individuals with possibly no experience with the deep squat.

- The studies don’t seem to take into consideration any of the physical impairments; someone with an ankle dorsiflexion restriction is going to squat much differently than someone with a ankle motor control problem.

- The definition of the deep squat is completely different in some papers (some have mentioned parallel femurs as a deep squat).

So you can’t expect too much from PubMed due to the inconsistent populations, lack of data on physical inputs, and a poorly defined task.

Same logic applies to the deep squat: if you ask someone to deep squat that doesn’t deep squat, it’s going to suck

Defining the Deep Squat

I’m going to call the deep squat simply a squat below parallel with a neutral spine.

If you can’t get below parallel with a neutral spine, you can’t do a deep squat as an exercise.

Getting below parallel with spine flexion is great if it’s unloaded (SFMA, PRI), but in this article I’m focusing on the act of loading the deep squat for strength, performance, & movement enhancement.

We Used to Always Squat

Tired of standing? Squat down.

Need to check something out or inspect an object? Squat down.

Hanging out, shooting the shit around a camp fire? Squat down.

This was the life for our ancestors (and for some of our current species in different cultures).

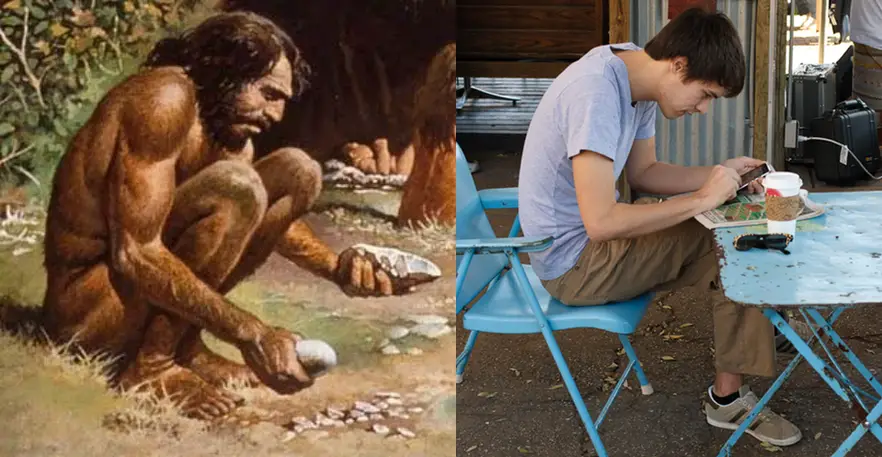

It’s Phylogenetics, the evolutionary history of our species. It’s our species’ “family tree” from the beginning of time.

The way our bodies have evolved over time has resulted in the movement pattern of the deep squat.

But it’s also Ontogenetics, the developmental history of an individual. It’s how the interaction of genetics, developmental programming, and environment affects the physical form throughout a lifespan.

I’ve mentioned in a previous post that we have culturally evolved at a rate that far surpases our physical evolution. Meaning, the world we live in is not made for our physical structures (chairs, shoes, school/work, technology, etc.).

This mismatch means that the person in front of you trying to squat should be able to squat (phylogenetics), but may not be able to because of the way they have interacted with their environment (ontogenetics).

For example, think of how a 4 year old can deep squat with no problem (phylogenetics), but the 50 year old, life-long sedentary, American desk jockey that can’t flex his hip past 90 degrees because of structural changes in his femur/acetabulum has no chance at a deep squat (ontogenetics).

But before you start analyzing your patient’s phenotype, you should first understand the benefits, risks, and drawbacks of the deep squat exercise.

A Visual Approach to Squatting

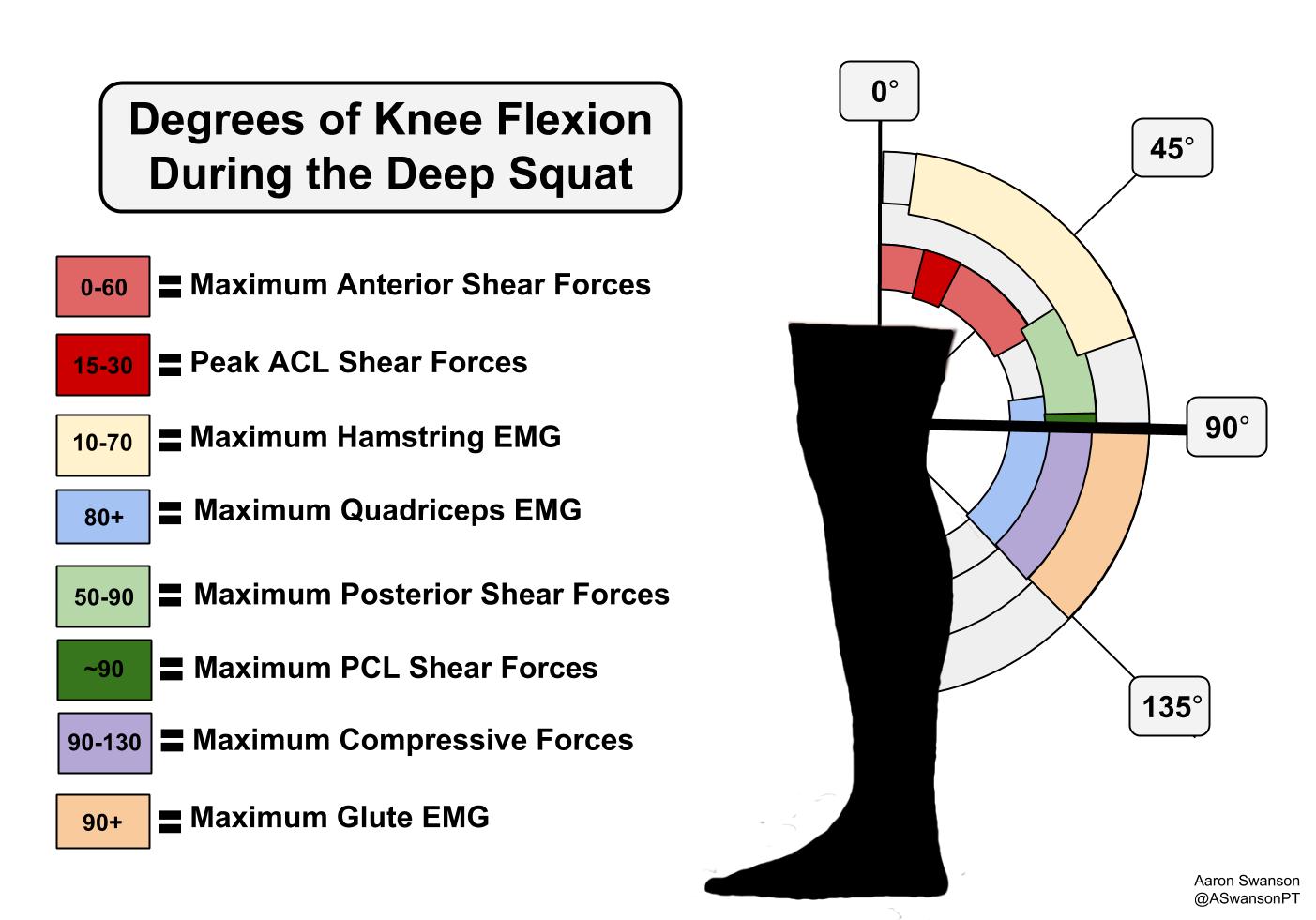

Before discussing the benefits and potential drawbacks of the deep squat, it’s best to understand exactly what is happening at the knee joint through varying degrees of knee flexion.

Here’s a diagram with the degrees of knee flexion and the associated forces/EMG activity.

This is based on several studies, listed below.

* Most studies don’t mention any activity beyond 135 degrees. So this is unknown and why there is nothing beyond 135

** It seems the force shifts from anterior to posterior between 50-60 degrees. This is why there is an overlap. Yes, I know it’s impossible to have both anterior and posterior shear forces at the same time.

Why it’s Good

It cures cancer!

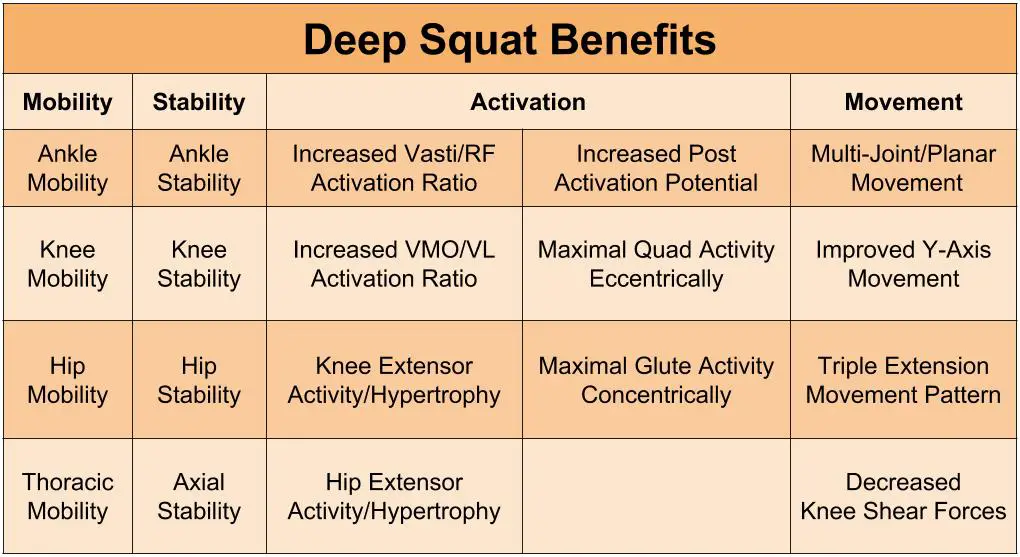

But seriously, the deep squat exercise has a ton of benefits (see chart below).

In general, the deeper the squat, the greater the quad and glute activation.

Plus, the deep squat spares the knee of shear forces and prevents ligamentous strain (see figure above). Since most lower extremity injuries involve weakness and aberrant shear forces, the deep squat can provide a great exercise to help reduce injury.

From a performance perspective, the deep squat provides a great exercise for increasing strength (legs, thighs, hips, core) and improving vertical (y-axis) movement efficiency.

Why it’s Bad

Ontogeny

The bad often comes from ontogeny. Everyone was able to squat as toddlers, but what they’ve done since then will influence what they can do now. In other words, the way someone has chosen to live their life may make the deep squat a bad exercise for them. Everyone was born to squat, but not everyone has grown to squat. This is due to the body adapting to life’s imposed demands (mechanotransduction, Wolffe’s Law, Davis’s Law, bioplasticity, etc.). Think of it as a structural SAID principle.

Someone that spends their life in an anterior pelvic tilt, wearing high heels, and sitting for 80 hours a week will have structural changes in their ankles, hips, and lumbo-pelvic area that will prevent them from a deep squat. This person would need years of specific training in attempt to reverse some of these adaptations to allow them to squat without compensations.

Compressive Forces

Another potential danger is the high compressive forces (tibiofemoral & patellofemoral) with a deep squat. Since there is an inverse relationship between shear and compression forces, the benefit of less shear is at a cost of more compression. For most, this isn’t a big problem if you apply the SAID principle and progress slowly. But for some it may be an issue.

Mobility Restrictions

In general, you should avoid prescribing the squat with people who do not have optimal mobility in their ankle, knee, and hip. Simply stated, if you do not have adequate mobility in these joints you will compensate and cause more harm than good.

Pathologies

Getting more specific and research-based, I would be very careful to squat with people who have: meniscus pathology, PCL pathology, hip impingement pathology (labral tear or bone spur), chondromalacia (depending on location of pathology), or advanced symptomatic osteoarthritis.

However, you should always treat the patient, not the script/image/anatomy.

But What About…

Many times in medicine, one of the first studies that come out on a subject becomes the most popular and becomes dogmatic. This happened with the 1961 research article by Klien. Klien reported that squatting was dangerous and increased laxity in the knee. Everyone jumped on the anti-deep squat bandwagon back then, and some are still dogmatically against the deep squat; even though Klien’s results have been refuted in many research articles since.

Here are some questions that many have about the squat and it’s safety.

Isn’t it Bad for Ligaments?

“Because the squat generated lower ACL strain compared with walking or jogging, it was concluded that the squat was a low risk exercise in rehabilitation of the ACL”. – Henning et al.

“In conclusion, basketball players and distance runners experienced a transient increase in anterior and posterior laxity during exercise. Power lifters doing squats did not demonstrate a significant change in laxity.” -Steiner et al

Isn’t it Bad for the Tissues Around the Knee?

“With increasing flexion, the wrapping effect contributes to an enhanced load distribution and enhanced force transfer with lower retropatellar compressive forces…Contrary to commonly voiced concern, deep squats do not contribute increased risk of injury to passive tissues.” -Hartman et al.

Isn’t it Bad for the Knee Cap?

This is basic physics (Force = Pressure x Area). There is increased compression with the deep squat, but there is also increased retro-patellofemoral contact area. Meaning the direct pressure on the knee cap is dispersed among a greater area, thus less focal retro-patellar forces. Just keep in mind the location of the retro-patella forces associated with the different degrees of knee flexion.

Isn’t it Bad for Knees?

“The squat does not compromise knee stability, and can enhance stability if performed correctly. Finally, the squat can be effective in developing hip, knee, and ankle musculature, because moderate to high quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocnemius activity were produced during the squat.” -Escamilla RF

“In conclusion, there is scant evidence to show that deep squats are contraindicated in those with healthy knee function.” -Schoenfeld BJ

Bottom Line

The squat can be a very valuable exercise for both rehab and performance.

The question isn’t about whether squatting below parallel is good for people. We know that squatting below parallel affords many benefits and few risks.

The questions has to deal with what the individual’s environment and lifestyle has done to them over time (ontogeny). What are the patient’s physical limitations and adapted structures developed to deal with? Which ones can you change? Which ones should you change?

Understanding the phases of the squat and the associated forces/EMG activity will help one prescribe the exercise more effectively.

Part I deals with understanding the deep squat. Part II will deal with implications for rehab, performance, and how to train it from the ground up.

Dig Deeper

Evolution:

Evolution goes much deeper than phylogeny and ontogeny. Ontogeny is an umbrella term that includes many more detailed concepts (e.g. phenotype plasticity, epigenome, etc.). Special thanks to the great professors who helped clarify some of these concepts for me: Daniel Liberman, Robert Boyd, Kathleen Smith, Jennifer Brisson, Jean-Jacques Hublin,

Squat Stuff:

Brad Schoenfeld has some of the best articles on the deep squat. Best place to start in my opinion. Scroll down for the articles – The Biomechanics of Squat Depth, Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance .

James Speck – 5 Reasons to Start Full Squatting

Chris Beardsley – Squat Depth for Glute Activation, Squat Depth

Bret Contreras – 7 Reasons to Squat Like a Man

Huffington Post – Nick English

Dean Somerset – Do You Need to Squat Deeply

Kevin Neeld – The Truth About Deep Squatting

Vincent St. Pierre – Are Deep Squat Safe

Nick Tumminello – 7 Reasons This is a Ridiculous Myth

Menno Henselmans – Partial ROM vs. Full ROM

Brent Brookbush – A Kinesiological Approach to the Overhead Squat (16 Video Series)

References

HENNING, C. E., M. A. LYNCH, and K. R. GLICK, Jr. An in vivo strain gage study of elongation of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am. J. Sports Med. 13:22-26, 1985.

Klein K. The deep squat exercise as utilized in weight training for athletes and its effects on the ligaments of the knee. J Assoc Phys Ment Rehabil 15: 6–11, 1961

Escamilla RF. Knee biomechanics of the dynamic squat exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 127–141, 2001.

Meyers E. Effect of selected exercise variables on ligament stability and flexibility of the knee. Res Q 42: 411–422, 1971.

Chandler T, Wilson G, and Stone M. The effect of the squat exercise on knee stability. Med Sci Sports Exerc 21: 299–303, 1989.

Bloomquist, K., H. Langberg, S. Karlsen, S. Madsgaard, M. Boesen, and T. Raastad. “Effect of Range of Motion in Heavy Load Squatting on Muscle and Tendon Adaptations.” European Journal of Applied Physiology 113.8 (2013): 2133-142.

Hartmann, Hagen, Klaus Wirth, and Markus Klusemann. “Analysis of the Load on the Knee Joint and Vertebral Column with Changes in Squatting Depth and Weight Load.” Sports Medicine 43.10 (2013): 993-1008.

Caterisano A, Moss RF, Pellinger TK, Woodruff K, Lewis VC, Booth W, Khadra T. The effect of back squat depth on the EMG activity of 4 superficial hip and thigh muscles. J Strength Cond Res. 2002 Aug;16(3):428-32.

Steiner M, Grana W, Chilag K, and Schelberg-Karnes E. The effect of exercise on anterior-posterior knee laxity. Am J Sports Med 14: 24–29, 1986.

Esformes, Joseph I., and Theodoros M. Bampouras. “Effect of Back Squat Depth on Lower-Body Postactivation Potentiation.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27.11 (2013): 2997-3000.

Salem, George J. et al. Patellofemoral joint kinetics during squatting in collegiate women athletes. Clinical Biomechanics 16:424-430, 2001.

Bryanton, Megan A., Michael D. Kennedy, Jason P. Carey, and Loren Z.f. Chiu. “Effect of Squat Depth and Barbell Load on Relative Muscular Effort in Squatting.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research26.10 (2012): 2820-828.

Schoenfeld BJ. Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. J Strength Cond Res 24: 3497–3506, 2010

Escamilla, RF, Fleisig, GS, Zheng, N, Lander, JE, Barrentine, SW, Andrews, JR, Bergemann, BW, and Moorman, CT. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33: 1552–1566, 2001a.

Walter, Chip. Last Ape Standing: The Seven-million Year Story of How and Why We Survived. New York: Walker &, 2013

Lieberman, Daniel. The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease. New York: Pantheon, 2013. Print

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.

May be the best squat article I’ve ever read. Great job

Great article….don’t want to repeat Zach…but one of the best I’ve read at the moment!

Interesting post. I was just wondering what you feel is the optimal degree of squatting is then? So we are clear, you are saying shear forces are more harmful than compressive forces?

What pathology is associated with increased compressive forces at the joint? Degenerative joint disease/OA?

Would a squat of 110degrees be an ideal degree to squat as it out of the shear force degree, but not at the full compressive maximum force?

I understand that more muscle recruitment exists as you squat lower, but at the risk of increasing compressive force, is it worth it to squat lower? So someone would not get as many gains from squatting lower, but may shield themselves from long term pathology?

I apologize in advance. It’s the answer I always hate getting myself…but the truth is, it depends on the individual.

The optimal degree of squatting is going to be specific to the individual based on many factors (exercise history, physical impairments, goals, etc.). For some clients, shear forces are potentially harmful (i.e. ACL). For others, compressive forces are potentially harmful (i.e. meniscus, DJD). But don’t get caught up on the pathology, it’s about the specific person in front of you.

If you apply the SAID principle carefully, people should be able to adapt to the compressive forces with time.

I’m sorry I can’t give you a hard answer, but there are too many variables to predict how everyone will respond to one exercise.

Beautiful article.

Watch out for mentioning anterior pelvic tilt as a common posture in life. You may be mistaken for being a Chiropractor who thinks psoas creates lordosis and that hip flexion slumped posture is anterior pelvic tilt! We, on the other hand, understand that sitting is a posterior pelvic tilt position that translates to the static posterior disc loading that precedes most disc injury.

I figure you just must treat a lot of table dancers who wear high heels for anterior pelvic tilt. That helps squatting depth BTW. Perhaps you could do an article on that next?

A fine piece of work. Well compiled! Useful to pass on to the miseducated.

Squat on!

One thing that I think people are forgetting is that in order to get into a deep squat you have to go through the ranges above it that have the peak shear forces. But the bottom of the squat doesn’t have the most “potentially” harmful force so if you can do a deep squat physiologically you might as well do it since by half reping you are still getting the most potentially harmful stresses.

what are your thoughts on the benefits or dangers of sqatting after a total knee replacement.

I think it depends on the individual. Did they squat before the TKR? Do they move well in their hips and ankles? Is their core stable/centrated? Do they have full knee ROM and quad control?

If the answer is yes to the above questions, then I think eventually they could squat safely. As the article points out, there are tons of benefits. But I’m not sure I would load it up and use it as a frequent exercise. Box squats with a posterior weight shift may be a better option to groove a more hip dominant movement pattern.

Thanks for the interesting squat artile. Would you explain what wrapping effect in specific?

It’s essentially more contact area, both front and back. in front the contact area increases as the tissues stretch (increasing passive support). in the back the contact area increases between the calf and hamstring, creating some support.

[…] Para leer el artículo original “The Deep Squat (Part 1 – The Good, The Bad, & The Not So Ugly)” haga clic aquí. […]

Haha! I hate squats. Being a tall guy I opt for leg presses and a combination of other exercises as well, but I’m willing ti give these deep squats a try just to see.

Thanks for this.