As many physical therapists have probably noticed, there is an increase in the amount of Crossfit athletes showing up in our clinics. This isn’t because it injures everyone. It’s because it’s becoming very popular and people love it.

We see the same thing happen during ski season and marathon season. It’s not necessarily the activity, it’s the increase in participation.

However, that’s not to say that it’s only an increase in participation that leads to a higher incidence of injuries. There are many other variables involved. Some of which can be improved upon to decrease the risk of injury.

I’ve noticed a few trends in my experience with Crossfit athletes. The crossfitters that tend to get hurt are the ones that seem to make the same 2 Mistakes:

1) Constantly Training to (and Past) Failure

2) Not Training Unilaterally Enough.

I think if Crossfit could improve on these 2 mistakes they would see a lot less people getting injured.

Crossfit isn’t the only activity where people get injured due to overtraining and asymmetry. Yet, they’re the only one with half the internet hating on them.

A Disclaimer

I have nothing against crossfit and don’t think it is ruining our species like some of my peers. In fact, I think Crossfit is great. Some of you might agree and some of you might be angry just by reading the word crossfit. But let me explain why I think it’s good.

Crossfit changes peoples lives. This is often an exact quote from many of my crossfit patients. I’ve had many patients who have lost tons of weight and become motivated to stay active because of Crossfit. This leads to changes in other parts of their lifestyle and improves their overall quality of life . Where personal trainers, spin classes, running, and traditional weightlifting have failed, Crossfit has succeeded. In a time where obesity and sedentary lifestyles are an epidemic, anything that gets people moving should be viewed favorably. I’d much rather have our population suffer with the occasional sore shoulder rather than die early from heart disease.

Some of these people would be sitting on their couch, watching tv, and eating bad food instead of getting a cardiovascular workout, socializing with other humans, while developing strength. I’d prefer our culture to have more musculoskeletal injuries and less morbidity & mortality.

Crossfit has popularized strength training. Too many people go on crazy diets, perform too much aerobic activity, or follow DVD fads to lose weight and get a metabolic burn. Crossfit has helped shift the emphasis to being strong. And strength is one of the best modalities for improving function, decreasing injuries, reducing morbidity, and decreases mortality (1-11).

Crossfit focuses on movements. Isolated muscle strengthening and machine based workouts are better than nothing, but they are vastly inferior when compared to multi-joint based movements. Crossfit has brought functional global movement exercises such as power lifts, olympic lifts, and kettlebells back to the mainstream (12-13, 22).

One last disclaimer is that I know not all “Boxes” are the same. Not all coaches are the same. And not all athletes are the same. Like every other activity or profession, there is a continuum of competence among crossfit gyms and coaches. I know there are a ton of very knowledgeable and talented Crossfit coaches out there already doing all the right things. Also, these mistakes are not just made by Crossfit coaches. There are many trainers, strength & conditioning coaches, physical therapists, and chiro’s making the same mistakes. The goal of this article is simply to bring awareness and offer solutions for 2 common mistakes that seem to happen often (not to attack crossfit as a whole).

Mistake #1 = Constantly Training to (and Past) Failure

I understand it’s important to test your limits every once in a while. And I know that when you’re in a competition or going for a PR many of the rules go out the window. But that doesn’t mean you should train like this every time.

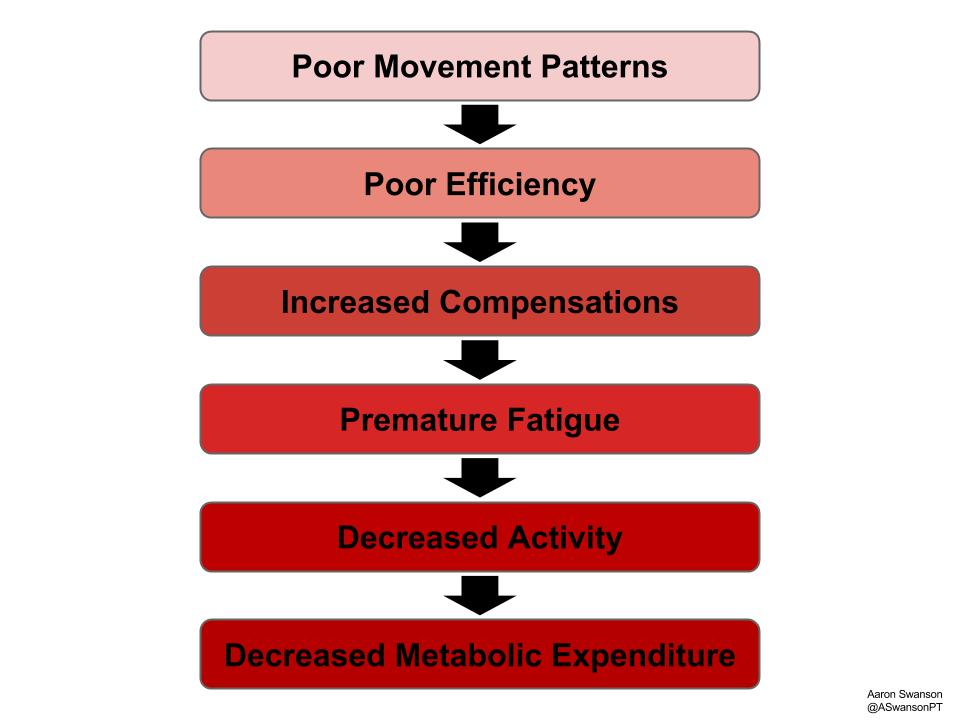

As fatigue sets in, good biomechanics, technique, and form start to fail. Everyone that has worked out to failure knows this and has felt this. Even if you haven’t experienced a fatigued state, there is more than just empirical evidence to support this hypothesis. Research has shown that mechanics and proper form go out the window in a fatigued state (14-18).

This is not only bad for performance, but more importantly, it is bad for your health. The more you continue to train in a fatigued state, the greater your risk for injury. This injury can either be an acute one or a chronic one.

Acute injuries are fairly easy to comprehend. Acute injuries occur instantaneously when the external load is greater than the tissues accepting it. It’s a cause and effect event.

Some examples of the acute injuries: A tired and sloppy deadlift with a rounded back on the 10th rep could damage your lumbar spine. A tired and sloppy snatch with forward shoulders and poor T-spine extension could lead to a labral tear. A tired and sloppy box jump with a knee caved in could lead to an ACL tear. In other words, it puts you at risk for an accident that occurs in a split second, but takes months to recover from.

Chronic injuries are a little more complicated and have to do with compensations and movement patterns.

If you groove the wrong movement patterns consistently you’ll set yourself up for an injury. Stay right.

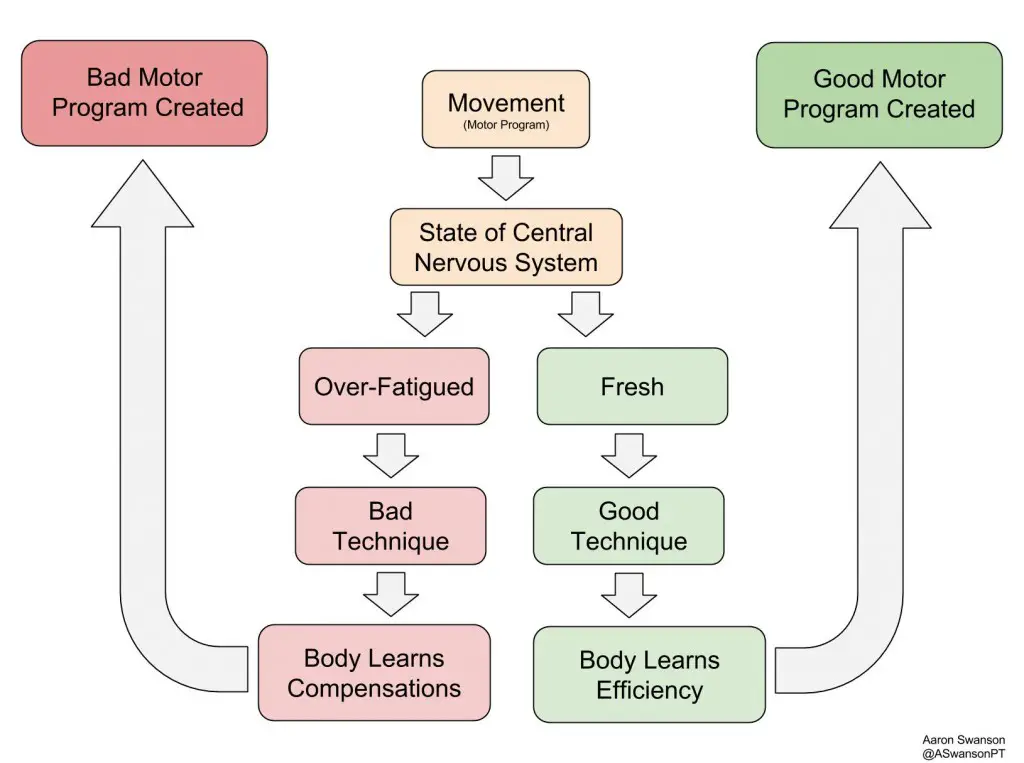

Movement patterns are the stored neurological “program” that resides in the brain. This “program” is what your nervous system fires out to make the right muscles fire at the right time to achieve the desired result. Performing exercises with poor form and inefficient muscle activation can teach your brain poor movement patterns. In other words, it can set in bad habits.

A long winded example might help. Lets take my favorite exercise done to failure – deadlifting. When you finish out those last 5 deadlifts with a rounded back because you were too tired to use the right muscles, your brain stores a new motor pattern. Now your brain has a new easier way to deadlift. Why lift with muscles when you can just lean on passive tissues like ligaments, joint capsules, and lumbar disks? In other words, your brain decides it’s better to save energy and rely on tissues that don’t require energy to get the job done (passive tissues). It decides lifting with a rounded back is a good idea. Stupid brain. You might be able to lift more weight (temporarily), but it will be at a cost to your spine. Overtime, this stress to your back accumulates and can lead to a slew of injuries (paraspinal strain, disk herniation, neurodynamic problems, SIJ strain, etc.).

MAYBE this is forgivable if it’s her last rep for a PR in a competition? But if this is how she normally deadlifts she’ll go from a Crosfitter to a patient very quickly.

So is it really worth it to sacrifice your movement to push it to the limit at every workout? Do you really need to do over 40 reps of every exercise on each set? What if you did more sets instead of more reps? Wouldn’t it be better to stop the set once technique starts to waver? What if you let people “ladder” down throughout the WOD instead of compensating through? Why not perform AMPRAP (As Many Perfect Reps As Possible) instead of just AMRAP?

A Suggestion

Better programming and an emphasis on improving technique as well as strength is something that many Crossfitters could benefit from.

Crossfit coaches can improve in this realm by emphasizing technique over numbers or metabolic expenditure. Assessing for poor technique and over-fatigue significantly decreases the risk of injury and will improve performance in the long run (you can’t make gains if you keep having to take time off because you’re injured). Coaches need to help athletes become aware of when their form goes bad and stop them from grooving bad movement patterns with compensatory muscle activity. And the WODs they develop can be programmed to avoid unnecessary fatigue and sloppy form on complex movements.

However, it’s important to understand that assessing for over-fatigue and poor technique is not just the coaches responsibility. The athletes need to be EDUCATED that when they can’t maintain form they are at a greater risk for injury and they need to stop. I think this is one of the biggest mistakes most crossfitters make. Many of them don’t understand this concept; they don’t understand the dangerous effects of not listening to your body and training with poor technique. Others are simply not aware of their poor form. Either way, this mistake needs to be addressed to decrease the risk of injury.

The results of grooving bad movement. The combination of these variables increases the risk of injury.

A warrior mentality often exists with Crossfitters. However, this mentality should adopt the idiom – live to fight another day.

Click Here for Part II

References

Strength is a Good Thing

1) Preethi Srikanthan, Arun S. Karlamangla. “Muscle Mass Index as a Predictor of Longevity in Older-Adults.” The American Journal of Medicine (2014)

2) Lauersen JB, Bertelsen DM, Andersen LB. The effectiveness of exercise interventions to prevent sports injuries: a systematic reviewand meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. (2014) Jun;48(11):871-7.

3) Harridge, Stephen D.r., Ann Kryger, and Anders Stensgaard. “Knee Extensor Strength, Activation, and Size in Very Elderly People following Strength Training.” Muscle & Nerve 22.7 (1999): 831-39.

4) Suetta, C., S. P. Magnusson, N. Beyer, and M. Kjaer. “Effect of Strength Training on Muscle Function in Elderly Hospitalized Patients.”Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 17.5 (2007)

5) Askling, C., J. Karlsson, and A. Thorstensson. “Hamstring Injury Occurrence in Elite Soccer Players after Preseason Strength Training with Eccentric Overload.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 13.4 (2003): 244-50

6) Nadler, Scott F., Gerard A. Malanga, Melissa Deprince, Todd P. Stitik, and Joseph H. Feinberg. “The Relationship Between Lower Extremity Injury, Low Back Pain, and Hip Muscle Strength in Male and Female Collegiate Athletes.” Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine 10.2 (2000): 89-97.

7) Peate, Wf, Gerry Bates, Karen Lunda, Smitha Francis, and Kristen Bellamy. “Core Strength: A New Model for Injury Prediction and Prevention.”Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology 2.1 (2007)

8) Orchard, J., J. Marsden, S. Lord, and D. Garlick. “Preseason Hamstring Muscle Weakness Associated with Hamstring Muscle Injury in Australian Footballers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine25.1 (1997): 81-85

9) Jankowski, C.m. “The Effects of Isolated Hip Abductor and External Rotator Muscle Strengthening on Pain, Health Status, and Hip Strength in Females With Patellofemoral Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial.”Yearbook of Sports Medicine 2012 (2012): 65-66.

10) Willson JD, Dougherty CP, Ireland ML, et al. “Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. (2005) Sep;13(5):316-25.

11) Hewett TE, Lindenfeld TN, Riccobene JV, et al. “The effect of neuromuscular training on the incidence of knee injury in female athletes. A prospective study.” Am J Sports Med. (1999) Nov-Dec;27(6):699-706.

Movement Based Exercise vs. Isolated Exercise

12) Gentil, Paulo, Saulo Rodrigo Sampaio Soares, Maria Claúdia Pereira, et al. “Effect of Adding Single-joint Exercises to a Multi-joint Exercise Resistance-training Program on Strength and Hypertrophy in Untrained Subjects.” Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 38.3 (2013): 341-44

13) Gottschall, Jinger S., Jackie Mills, and Bryce Hastings. “Integration Core Exercises Elicit Greater Muscle Activation Than Isolation Exercises.”Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 27.3 (2013): 590-96

Exercising in Fatigued State

14) Cortes, Nelson, Eric Greska, Roger Kollock, Jatin Ambegaonkar, and James A. Onate. “Changes in Lower Extremity Biomechanics Due to a Short-Term Fatigue Protocol.” Journal of Athletic Training 48.3 (2013): 306-13.

15) Santamaria, Luke J., and Kate E. Webster. “The Effect of Fatigue on Lower-Limb Biomechanics During Single-Limb Landings: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 40.8 (2010): 464-73.

16) Barnett S Frank, Christine M Gilsdorf, Benjamin M Goerger, et al. “Neuromuscular fatigue alters postural control and sagittal plane hip biomechanics in active females with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.” Sports Health (2014) Jul;6(4):301-8

17) Quammen D, Cortes N, Van Lunen BL, et al. “Two different fatigue protocols and lower extremity motion patterns during a stop-jump task.” J Athl Train. (2012) Jan-Feb;47(1):32-41.

18) Pau M, Ibba G, Attene G. “Fatigue-induced balance impairment in young soccer players.” J Athl Train. (2014) Jul-Aug;49(4):454-61.

Imbalances Are Bad

19) Knapik, J. J., C. L. Bauman, B. H. Jones, J. Mca. Harris, and L. Vaughan. “Preseason Strength and Flexibility Imbalances Associated with Athletic Injuries in Female Collegiate Athletes.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 19.1 (1991): 76-81

20) Baumhauer, J. F., D. M. Alosa, P. A. F. H. Renstrom, S. Trevino, and B. Beynnon. “A Prospective Study of Ankle Injury Risk Factors.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine 23.5 (1995): 564-70.

21) Common Sense & Conventional Wisdom (>6 million years BC)

Motor Learning

22) Cook, Gray. Movement: Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, and Corrective Strategies. Aptos, CA: On Target Publications, 2010. Print.

23) Schmidt, Richard A., and Craig A. Wrisberg. Motor Learning and Performance: A Problem-based Learning Approach. Champaign,IL: Human Kinetics, 2004.

24) Williams, L. R., McEwan, E. A., Watkins, C. D., Gillespie, L., & Boyd, H. (1979). Motor learning and performance and physical fatigue and the specificity principle. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Sciences, 4, 302-308.

“The body does not have the capacity to learn movement patterns when highly stressed/fatigued. This factor is not related to the specificity of training principle associated with overload adaptation in energy systems. The specificity principle of physiological adaptation does not apply to motor learning. To learn skilled movement patterns that are to be executed under fatigued conditions, that learning has to occur in non-fatigued states” — Williams 1979

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.

Great article, I try to convey this to some of our crossfitter or even powerlifter patients, its like practicing a bad golf swing, if the bio mechanics aren’t there, you’re just making something permanent no perfect.Practice makes permanent….i deal with biomechanics and movement discussion with my physio daily…great read thanks

This is the most articulate non-crossfit bashing article I have ever read. Excellent.