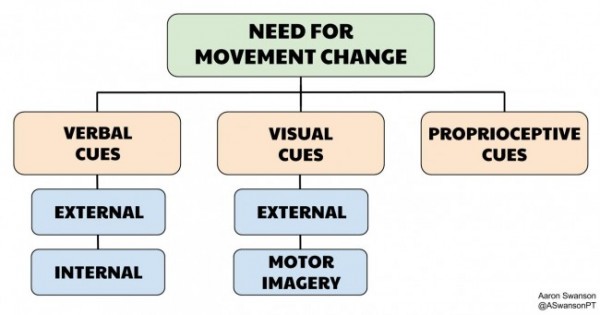

The minimal effective dose rule goes into effect here. You want to achieve the necessary movement change with the minimal amount of sensory change. If you throw too many different cues (verbal, visual, proprioceptive) at the same time, it will clog up the system and wear down the patient. As mentioned in the previous articles, it comes down to attention economy – you always want the movement to have the spotlight, not the cues.

So where do you start?

The answer to this question is going to change dramatically based on the task and the individual. Between these two factors, there are a ton of variables (e.g. moving parts, degrees of freedom, environment, load input, tissue stress, exercise history, learning preference, sensory integration, expectations, motivation, etc.). Each variable have a profound impact on how they respond to coaching and cues.

So what do you do? How do you cut down the variables and choose which cue to use? How do you manage the movement change?

Four Ways to Manage Coaching & Cueing

So unless you have a homogeneous patient population, it is important to have multiple different cueing methods to choose from. This will allow you to better match the individual with a specific cue that achieves the movement outcome you desire. To become proficient at the various cueing methods you should do these 4 things:

- Understand the different types of cues (Parts 2–6)

- Build a library of cues – spend time learning cues/perspectives from others (use social media, read articles, get many different types of movement experiences)

- Realize what phase of learning the patient is in

- Get experience and practice

Since 1 has already been discussed in this series and 2 can only be achieved independently, we’ll focus on 3 and 4 in this post.

3) Phases of Learning

There are many ways to breakdown learning phases. Here are 3 common paradigms that I use in my practice. By no means is this list exhaustive or detailed, but it should provide a diving board for deeper knowledge.

Keep in mind this is not a general statement about the patient, it’s a specific transient phase that fits the individual and the current task.

Transtheoretical Model

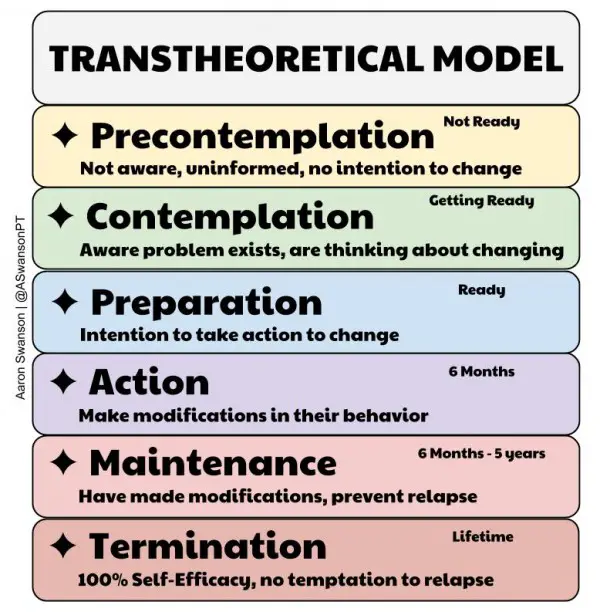

Sometimes I’m jealous of trainers and performance PTs. Working with a motivated population that has a habit of exercising on a regular basis (action/maintenance phase) seems like a nice way to spend your days. However, in rehab it’s often the opposite. We are often presented with unmotivated patients that have no idea they need to take an active role in a process that they know nothing about (precontemplation). Many patients come to see us in rehab so that we can “fix” their pain or pathoanatomical diagnosis.

For these patients, this model works very well. It gives you an approach to take them from precontemplation to maintenance all in one bout of PT. Understanding the current phase of learning the patient is in is important because there’s no point in teaching someone a DNS Side Lift (active) if they don’t even understand why it’s necessary for them (precontemplation/contemplation).

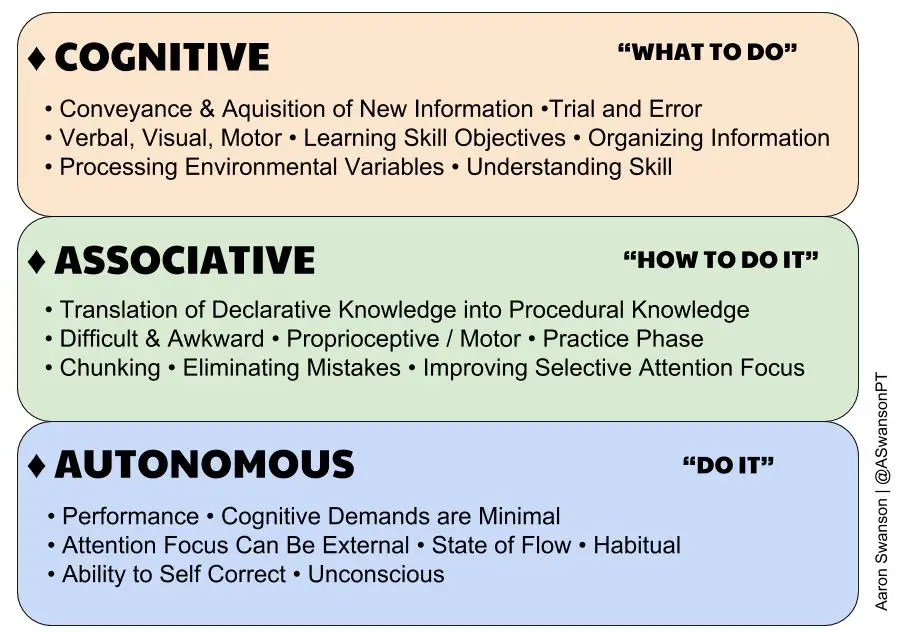

Fitts & Posner 3 Stages of Motor Learning Model

This is one of the most common models for motor learning. And for good reason, it provides a concise method for categorizing your patient into a specific learning phase. It doesn’t take into consideration the psychosocial inputs that the TTM does, but it does give an easy way to assess the motor learning aspect.

It’s pretty straight forward. Just simply move them down the list. But just be aware that the associative phase is often frustrating and takes time to get through. Rushing through this stage and assuming the patient has automatic control is how you develop bad movement patterns and future injuries.

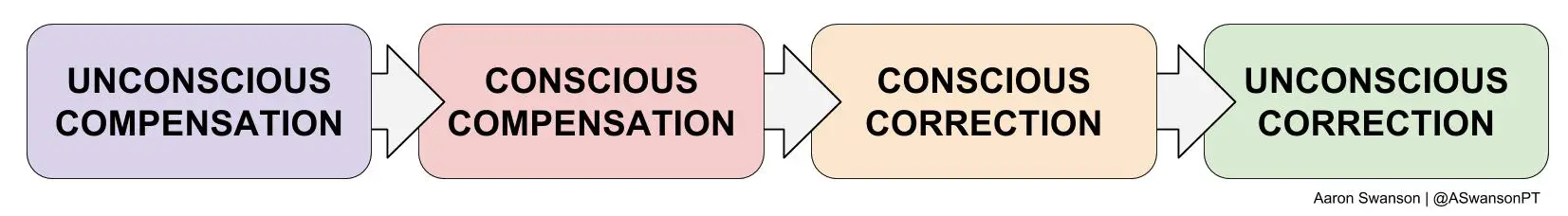

Movement Compensation

I’m not sure where I heard this. Maybe from Gray Cook, Greg Rose, SFMA, or TPI? But it provides a simple flow that you can use to educate your patients. It’s very user friendly and utilizes language that is easy for the patients to understand. You can think of it as a combination of the above models.

4) Practice

- Skill = Knowledge + Experience

Attaining the knowledge of coaching and cueing is a great start. But to develop the skill you need focused practice (experience).

To improve your focus during coaching sessions it’s important to perform your mental due diligence and ask yourself questions before, during, and after the movement. This will help narrow the variables and improve your cue selection.

Below are some basic questions I ask myself when coaching movement.

Four Questions Before the Movement

- 1) Is this for a novice, intermediate, or an expert?

- 2) Is it a completely new movement or is it a refining or chunking of a previous one?

- 3) Is this a simple movement or a complex movement?

- 4) Is this for motor control/learning/technique, body awareness, specific isolated muscle activation, performance, movement restoration, or just general exercise for global health?

After You Answer These Questions

Educate the patient on what you want them to do. Give them the details, the name of the exercise, why it’s good for them, why you want them to do it, what it accomplishes, and what you want them to achieve (later on where they should direct their attention focus).

Two Questions After the Movement

1) Did it look good?

Assessing the body segments, angles, timing, and overall motion is the easiest way to ensure proper movement. If it looks bad, then it needs to be cleaned up with some coaching. If it looks good, then it probably doesn’t need any cues.

However, it’s also important to realize that perfect kinematics does not equal perfect movement patterns. Aberrant motor patterns, excessive muscle tone, substitutions, subtle de-centrations, and compensations can all occur while the movement kinematically looks good. So how you check this?

2) Where did they feel it?

With this question you can find out if the patient actually owns the movement. If they can feel the movement with the right body parts than you can be sure that they get it from both the bottom-up and the top-down levels. If they can’t feel it, them there’s a disconnect and there will likely be compensations occurring somewhere along the kinetic chain.

Avoid Over Coaching

Sometimes you can clog up the system and confuse the patient by giving them too many cues and too many things to think about, especially for beginners, new movements, or complex movements.

It’s important to let them first perform a couple reps without any extra input from your mouth. The patient needs to be given a chance to feel and process the movement. The person coaching needs to take some time to see what the most egregious fault is without biasing the movement.

Summary

The good thing about movement is that we can easily assess it. If you’re not getting the desired result, just try a different cue. And if different types of cues aren’t working, the problem lies in the practitioner not the patient (pick a different exercise).

If there is one take home from this series it’s this: changing movement or developing a skill requires two things: focus and feedback. It’s your job as a clinician to provide your patients with these two things.

Coaching & Cueing

Part I – Intro

Part II – The Categories

Part III – Verbal Cues – External

Part IV – Verbal Cues – Internal

Part V – Visual

Part VI – Proprioceptive

Part VI – Summary