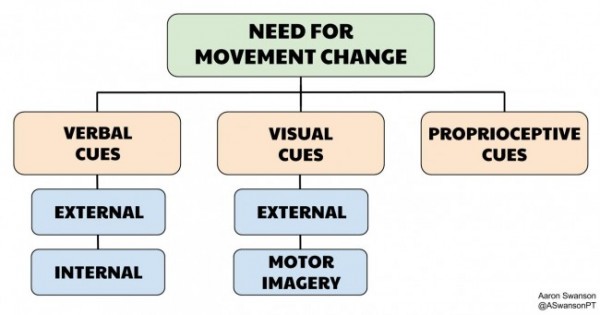

Unfortunately, the rise in popularity of external cueing has led to a bad stigma of internal cueing. After reading the last article in this series you may be thinking why would you ever internally cue someone?

Here’s why:

Benefits of Internal Cues

- Improved Mapping / Body Awareness

- Creates Reference Points

- Teaching Technique/Form

- Muscle Activation – Increased EMG

- Alter Synergistic Muscle Activation

- Mindfulness

3 Topics in This Article

- Why internal cueing is important

- The concepts/science behind internal cueing and body awareness

- Elaboration of the benefits

Disclaimer

Unfortunately, the concepts behind internal cueing aren’t quite as simple as those of external cueing. Many of these concepts (attention, perception, neuroplasticity, mindfulness, interoception, neuroscience, embodiment, etc.) could each be an article series on their own. I’ll try to summarize them within the context of internal verbal cueing for movement, but it may be worthwhile to dig deeper in order to better understand these concepts.

Why Internal Cueing is Important

It’s Not Always About Motor Learning or Performance

One of the major concepts that is often overlooked is the fact that most of the research and arguments for external cueing has been done through the lens of motor learning and performance. But what about all the other variables that we work on with our patients?

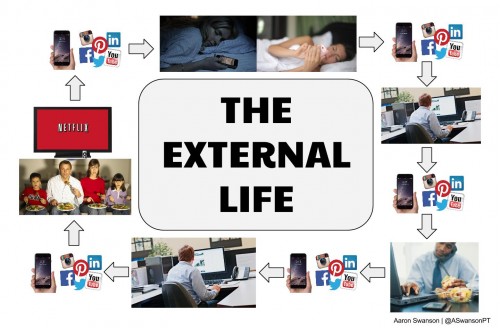

If you remember from Part I, not everyone is trying to PR their deadlift or improve their free throw percentage. And not everyone has a history of athletic movement and weight lifting. There are beginners out there that have no idea what their body is doing when they try to accomplish a physical task. There are people who haven’t tried a new movement in decades. There are people who only think externally all day. There are people who have simply lost their body awareness.

So why would you use the same cue for someone who is trying to max out their deadlift that you would for someone who can’t even intrinsically feel their pelvis position on the table?

Living with constant external stimulus. And some people even stay external as they exercise by watching tv or listening to podcasts.

Why is Body Awareness Important

To reiterate, with internal cueing we’re not talking about performance or even motor learning. We’re talking about body awareness and control. You can only control what you can feel. And if you can’t intrinsically feel a part of your body, that’s a problem.

If this were any other sensory input this wouldn’t even be a question.

Imagine you are a piano teacher. You are teaching your student the notes of the C scale. If you started playing the notes on a piano one by one, and your student couldn’t hear anything when you hit the E note, you would consider that a big problem. If you went to a museum and could see everything but the color orange, you would consider it a big problem. If you went out to a restaurant…you get the point. So why do we give our bodies a free pass and just move on despite the fact that we may be missing an essential sensory component?

For some patients, intrinsic cueing is a prerequisite for more complex motor tasks and external cueing. It’s like understanding the notes on the piano before you try to learn classical music.

You can’t teach C major if they can’t hear the E note. You can’t teach complex movement if they can’t feel their body.

Semantics – Body Awareness

In the spirit of simplification, I am going to use the term body awareness to express the concept of feeling your body and the associated internal forces. It’s your brain’s ability to “feel” the internal sensory input.

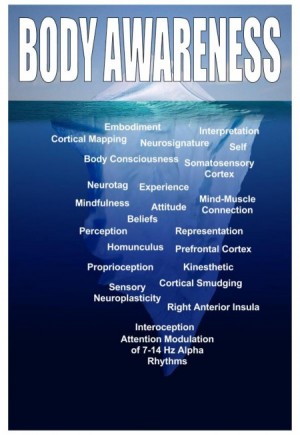

However, it is important to keep in mind that just because we are simplifying this concept for the sake of the topic, it does not mean it is a simple concept.

- “Body awareness is hypothesized as the product of an interactive and dynamic, emergent process that a) reflects complex afferent, efferent, forward and back-projecting neural activities, b) includes cognitive appraisal and unconscious gating, and c) is shaped by the person’s attitudes, beliefs, experience and learning in a social and cultural context.”-Wolf Mehling

Since most people don’t even see the top of the internal cueing iceberg, arguing about what’s at the bottom is beyond the scope of this article.

Body Awareness Concepts

Attention for Wiring

- “Remember that it’s an attention economy in the brain: where we put our focus determines the wiring that we create.” — David Rock

There is an overwhelming amount of input that is flooding the brain at every moment (visual, auditory, internal processing, viscera, proprioceptive, smell, mechanoreceptors, thoughts, beliefs, etc.). To avoid going into a seizure, we filter much of this information in order to achieve our “normal” state of being. One of the things we use to modulate this information is our attention focus.

Body awareness is essentially the attention focus of internal sensory information. This attention focus allows us to “feel” our bodies.

Right now there is a plethora of internal sensory information that is ignored so that you can use your attention to read this article. But if you bring your focus towards feeling your hands you will all of a sudden become “aware” of them. Your hands have not changed, but your attention focus has, which has subsequently changed your brain.

This isn’t just a fleeting perceptual change. It’s a change in the neural connections of your brain.

Just like muscles, each time you activate a neural wiring it demands blood flow and nutrients. This promotes growth and adaptation. So activating specific neural connections through internal sensory attention focus will “strengthen” one’s body awareness. It will build the central synaptic body awareness.

But it’s not just the “strength” of these neural connections that matters. The more important part is what these connections represent.

This is essentially what happens in your somatosensory cortex when you focus your attention on your body

Homunculizing

By paying attention to internal sensory information, your brain can map a better homunculus. This improved representation gives the brain a better reference point from which it can select the optimal motor strategy for a task.

This concept has been discussed over the years as Cortical Smudging.

Without an attention focus of a bottom-up feedback, a pre-selected top-down pattern could be negatively affected. When top-down references are “off” it causes dysfunctional bottom-up feedback. When this happens we usually see pain and poor movement.

You first need to be able to feel the isolated raised dots before you can put them together to understand the sentence.

An example of this concept is learning braille. If you just run your fingers over the bumps without paying attention to what you’re feeling, you’ll never learn. You need the internal cue to “feel” the bottom-up sensory information so that your brain can start to map out the necessary reference points. An external cue of push into the paper would not help you read braille.

- “Directing attention to sensory stimulation can increase perceptual sensitivity and modulate neuronal activity” -Heidi Johansen-Berg

Mindfulness

Essentially, internal cues help to improve body awareness through mindfulness. Research shows mindfulness is successful for treating various dysfunctions, including stress related responses (anxiety, depression, chronic pain, etc.).

We know that stress increases the “noise” in the brain and makes it more difficult to hear other stimuli (i.e. your body). We see this in the clinic when our patients are struggling to perform a simple exercise despite all the external cues.

So how do you quiet the “noise” so that the patient can somatically listen to themselves?

Research has shown that paying attention to internal body sensations can help to modulate the alpha rhythms of the brain can quiet the “noise”, thus making it easier to feel internal sensations.

Practicing mindfulness with internal cues is like taking them from a rock concert in a small club to an outdoor symphony.

Benefits of Internal Cueing

Internal Cues Provide the Map

One of the factors that influences how we move now is our history (immediately and long term). And this is where internal cueing can be useful.

Take the deadlift for an example. If someone has had back pain, sits for the majority of their day, hasn’t paid attention or felt their glutes in years, and barely works out, then they will not have their hips mapped out very well in their brains. They won’t have the body awareness to know the difference between their hips moving and their lumbar spine moving. Often in the clinic you see these people perform a bridge with an excessive amount of lumbar extension tone. You ask them where they feel it, and they say their back. Should you be progressing this person to a deadlift with external cues?

Without a proper body map, the motor output will be compromised. The feedback hasn’t been wired properly, so the feedforward output won’t have a strong reference point. It’s as if the body will bypass the poorly mapped area (hips) and rely on other areas that are more robustly mapped (back)

This is why I think internal cues to improve body awareness are important. You have to make sure people can intrinsically feel and control their body – which would represent adequate cortical mapping.

Once they have this body map awareness, you can confidently progress them to more complex motor tasks and use external cues to achieve the desired output.

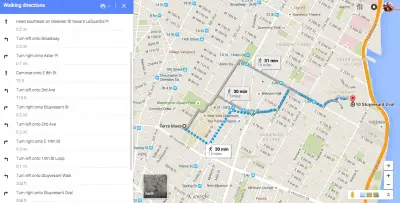

- Internal cues provide the map, external cues give you the directions

Before you can follow specific directions (external cues), you first need to know what town you’re in (internal cues).

Changes Focus / Distraction from Pain

Another benefit that I’ve seen clinically from internal cueing is the simple distraction it provides patients. Often times people will obsess about their pain and it becomes a part of every movement. Instead of feeling the rest of their body, they focus on the painful area with all of their attention. Thus, the brain writes more painful wiring for that area. It’s a vicious cycle.

Current research supports this empirical evidence – people in chronic pain have difficulty shifting their attention away from the painful area.

Having people focus on internal cues away from the painful site can not only distract them from pain, but it will help the brain wire pain-free movement connections. And more pain-free movement connections is a great thing for anyone in pain.

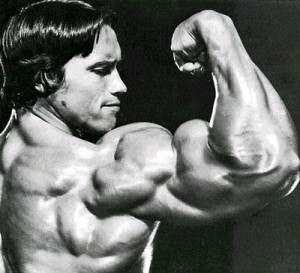

It Worked for Arnold and the Brosephs

7 time Mr. Olympia, Arnold Schwarzenegger, has discussed his use of internal cues and motor imagery to increase local hypertrophy. And I think we can all agree that he’s been fairly successful when it comes to local hypertrophy.

Ask any bro at the gym what they’re focusing on and the answer will likely be the local muscles. But don’t judge them, if they’re just trying to increase local hypertrophy then they’re doing the right thing. We now know that internal cues aren’t great for complex movements due to co-contraction and the constrained hypothesis theory, but they do lead to increased EMG activity.

Ways to Influence the Internal Map

Internal verbal cues may be enough to help change your patient’s internal map. But when this fails, there are many other options to help facilitate the brain change and improve body awareness.

- Attention Focus Internal Cues

- Body Scan / Mindfulness

- Exercise Modification (isolated, slow, groundwork, load, etc.)

- Manual Therapy / Acupuncture

- Dissociation Exercises

- Stretching (Dynamic & Static)

- Somatics (Qi Gong, Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais, Yoga, etc.)

Summary

If you’re working in high level athletics with people who need to improve performance, then external cues are preferred. However, if you’re working with a much wider population that includes non-athletic people, people in pain, or people that live too externally, then internal cues may be very useful in improving movement and/or pain. If you are unsure if this type of cueing is needed, simply ask your patient during an exercise – “where do you feel this?”.

Coaching & Cueing

Part I – Intro

Part II – The Categories

Part III – Verbal Cues – External

Part IV – Verbal Cues – Internal

Part V – Visual

Part VI – Proprioceptive

Part VI – Summary

References

Pincivero, Danny M., and William S. Gear. “Quadriceps Activation and Perceived Exertion during a High Intensity, Steady State Contraction to Failure.” Muscle & Nerve Muscle Nerve 23.4 (2000): 514-20.

Cafarelli, Enzo. “Peripheral Contributions to the Perception of Effort.”Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 14.5 (1982)

Lind, Erik, Amy S. Welch, and Panteleimon Ekkekakis. “Do ‘Mind over Muscle’ Strategies Work?” Sports Medicine 39.9 (2009): 743-64

Lewis, Cara L., and Shirley A. Sahrmann. “Muscle Activation and Movement Patterns During Prone Hip Extension Exercise in Women.”Journal of Athletic Training 44.3 (2009): 238-48.

Snyder, Benjamin J., and James R. Leech. “Voluntary Increase in Latissimus Dorsi Muscle Activity During the Lat Pull-Down Following Expert Instruction.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 23.8 (2009): 2204-209.

Clark, B. C., N. K. Mahato, M. Nakazawa, T. D. Law, and J. S. Thomas. “The Power of the Mind: The Cortex as a Critical Determinant of Muscle Strength/weakness.” Journal of Neurophysiology 112.12 (2014): 3219-226.

Yao, Wan X., Vinoth K. Ranganathan, Didier Allexandre, Vlodek Siemionow, and Guang H. Yue. “Kinesthetic Imagery Training of Forceful Muscle Contractions Increases Brain Signal and Muscle Strength.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7 (2013)

Ranganathan, Vinoth K., Vlodek Siemionow, Jing Z. Liu, Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H. Yue. “From Mental Power to Muscle Power—gaining Strength by Using the Mind.” Neuropsychologia 42.7 (2004): 944-56.

Kerr, Catherine E., Stephanie R. Jones, Qian Wan, et al. “Effects of Mindfulness Meditation Training on Anticipatory Alpha Modulation in Primary Somatosensory Cortex.” Brain Research Bulletin 85.3-4 (2011): 96-103.

Mehling, Wolf E., Judith Wrubel, Jennifer J. Daubenmier, Cynthia J. Price, Catherine E. Kerr, Theresa Silow, Viranjini Gopisetty, and Anita L. Stewart. “Body Awareness: A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Common Ground of Mind-body Therapies.” Philos Ethics Humanit Med Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 6.1 (2011)

Lebon, Florent, Christian Collet, and Aymeric Guillot. “Benefits of Motor Imagery Training on Muscle Strength.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 24.6 (2010): 1680-687.

Fox, Carl Gabbard Ashley. “Using Motor Imagery Therapy to Improve Movement Efficiency and Reduce Fall Injury Risk.” Journal of Novel Physiotherapies J Nov Physiother 03.06 (2013)

Masters, R. S. W. “Knowledge, Knerves and Know-how: The Role of Explicit versus Implicit Knowledge in the Breakdown of a Complex Motor Skill under Pressure.” British Journal of Psychology 83.3 (1992): 343-58.

Johansen-Berg, Heidi, and Matthews P. “Attention to Movement Modulates Activity in Sensori-motor Areas, including Primary Motor Cortex.” Experimental Brain Research 142.1 (2002): 13-24

Gomez-Ramirez, Manuel, Natalie K. Trzcinski, Stefan Mihalas, Ernst Niebur, and Steven S. Hsiao. “Temporal Correlation Mechanisms and Their Role in Feature Selection: A Single-Unit Study in Primate Somatosensory Cortex.” PLoS Biol PLoS Biology 12.11 (2014)

Clark, B. C., N. K. Mahato, M. Nakazawa, T. D. Law, and J. S. Thomas. “The Power of the Mind: The Cortex as a Critical Determinant of Muscle Strength/weakness.” Journal of Neurophysiology 112.12 (2014): 3219-226

Stoykov, Mary Ellen, and Sangeetha Madhavan. “Motor Priming in Neurorehabilitation.” Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy 39.1 (2015): 33-42.

Wondrusch, C., and C. Schuster-Amft. “A Standardized Motor Imagery Introduction Program (MIIP) for Neuro-rehabilitation: Development and Evaluation.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7 (2013):

Kerr, Catherine E., Matthew D. Sacchet, Sara W. Lazar, Christopher I. Moore, and Stephanie R. Jones. “Mindfulness Starts with the Body: Somatosensory Attention and Top-down Modulation of Cortical Alpha Rhythms in Mindfulness Meditation.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7 (2013)

Iriki, Atsushi. “Faculty of 1000 Evaluation for Temporal Dynamics of Plastic Changes in Human Primary Somatosensory Cortex after Finger Webbing.” F1000 – Post-publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature (2006)

Merzenich, Michael M., Randall J. Nelson, Michael P. Stryker, Max S. Cynader, Axel Schoppmann, and John M. Zook. “Somatosensory Cortical Map Changes following Digit Amputation in Adult Monkeys.” J. Comp. Neurol. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 224.4 (1984)

Lazar, Sara W., Catherine E. Kerr, Rachel H. Wasserman, Jeremy R. Gray, Douglas N. Greve, Michael T. Treadway, Metta Mcgarvey, Brian T. Quinn, Jeffery A. Dusek, Herbert Benson, Scott L. Rauch, Christopher I. Moore, and Bruce Fischl. “Meditation Experience Is Associated with Increased Cortical Thickness.” NeuroReport 16.17 (2005): 1893-897.

Farb, N. A. S., Z. V. Segal, and A. K. Anderson. “Mindfulness Meditation Training Alters Cortical Representations of Interoceptive Attention.”Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 8.1 (2012): 15-26

Craig, Ad (Bud). “Interoception: The Sense of the Physiological Condition of the Body.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology 13.4 (2003): 500-05.

Mehling, Wolf E., Viranjini Gopisetty, Jennifer Daubenmier, Cynthia J. Price, Frederick M. Hecht, and Anita Stewart. “Body Awareness: Construct and Self-Report Measures.” PLoS ONE 4.5 (2009)

Hamilton, Roy H., and Alvaro Pascual-Leone. “Cortical Plasticity Associated with Braille Learning.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2.5 (1998): 168-74.

Polley, D. B. “Perceptual Learning Directs Auditory Cortical Map Reorganization through Top-Down Influences.” Journal of Neuroscience 26.18 (2006): 4970-982.

Arnsten, Amy F. T. “Stress Signalling Pathways That Impair Prefrontal Cortex Structure and Function.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience Nat Rev Neurosci 10.6 (2009): 410-22

Roosink, Meyke, Bradford J. Mcfadyen, Luc J. Hébert, Philip L. Jackson, Laurent J. Bouyer, and Catherine Mercier. “Assessing the Perception of Trunk Movements in Military Personnel with Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain Using a Virtual Mirror.” PLoS ONE PLOS ONE 10.3 (2015)

Arntz, Arnoud, Laura Dreessen, and Harald Merckelbach. “Attention, Not Anxiety, Influences Pain.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 29.1 (1991): 41-50.

Garrison, Kathleen A., Juan F. Santoyo, Jake H. Davis, et al. “Effortless Awareness: Using Real Time Neurofeedback to Investigate Correlates of Posterior Cingulate Cortex Activity in Meditators’ Self-report.” Front. Hum. Neurosci. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 7 (2013)

Schabrun, Siobhan M., Edith L. Elgueta-Cancino, and Paul W. Hodges. “Smudging of the Motor Cortex Is Related to the Severity of Low Back Pain.” Spine (2015)

Rock, David. Quiet Leadership: Help People Think Better — Don’t Tell Them What to Do: Six Steps to Transforming Performance at Work. New York: Collins, 2006.

Qi Gong Classes with Tina Zhang. New York City. 2014-2015.

Alexander Technique Inservice – Emily Whyte. New York City. 2015.

Feldenkrais Workshop – Art & Science of the Method with David Zemach-Bersin. New York City. 2015.

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.