In Part I you learned the concepts behind upward rotation and the overhead shoulder. This article builds off of these concepts and will show you how to properly assess and treat for the overhead shoulder.

I cannot emphasize enough how important a thorough assessment is before prescribing overhead shoulder exercises. Without an assessment to determine any impairments or movement dysfunctions you will not be able to properly prescribe the correct exercises. Before someone starts overhead movements you should make sure they’re clear in all of the overhead shoulder characteristics (Part I). Failure to do so could result in injury.

However, a full biomechanical assessment is beyond the scope of this article. Only general shoulder type and posture will be addressed in the assessment.

Assessment

Once you have cleared their shoulder biomechanics you can start to look back at the movement and shoulder type.

There are several ways to assess the scapula position and shoulder type. The Kibler Scapula Classification is one of the more common assessments.

However, as we learned in part I, the scapula is only part of the kinetic chain.

You need to also look globally. And lucky for us, one of the best ways to assess global shoulder types is by simply looking at posture.

Posture

Don’t just look at the glenohumeral joint, or even just the scapula. You need to start at the center and work your way out. Each level will determine what part of overhead training the patient will need to focus on.

Lumbar Spine: Look for the degree of their lordosis/anterior pelvic tilt. If someone is hyperextended and hinges at the T-L junction you will need to address their anterior core before going overhead.

Thoracic Spine: You will usually either see a kyphotic thoracic spine or a flat thoracic spine. Both cases will have difficulty stabilizing their scapula. This needs to be addressed so that the scapula can move efficiently. The scapula can be viewed like the patella; “it’s not the train that needs fixin’, its the tracks”.

Clavicle: Due to its attachments, it will be a giveaway for the scapula. You want to see a 6-20° upslope.

Scapula: This is the biggest giveaway. The scapula is the “liaison” between the arm and the trunk. But remember it moves in many planes, not just forward in back.

• Anteriorly or Posteriorly Tilted (Sagittal)

• Upward or Downwardly Rotated (Frontal)

• Elevated or Depressed (Frontal)

• Internally Rotated (Winged) or Externally Rotated (Transverse)

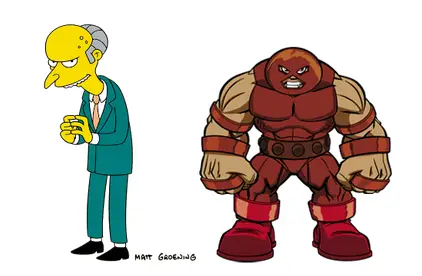

I’m not sure Mr. Burns has ever gone overhead. Juggernaut’s shoulder are so elevated he has no neck.

Even a quick global view will give you a good indication. For example, look at the picture to the left.

Mr. Burns is a mess. All his time obsessing about money and abusing his employees has left his shoulders depressed and his thoracic spine kyphotic.

On the other hand, Juggernaut’s uncontrollable rage has left his shoulders so high he appears to have no neck.

These two would respond completely differently to an overhead program and require completely different exercises and cues.

Shoulder Flexion / Abduction

Once you have a good postural/static assessment you can then assess how they move dynamically when going overhead. This movement pattern assessment will be a very valuable insight to their compensatory strategies.

Have the patient flex and/or abduct their arms all the way overhead. Look for fluid motion. It shouldn’t be a struggle for someone to get their arm overhead.

You want to look for similar things that you do during the postural assessment, but you can focus on 3 things.

Uneven hands can be seen in patients that don’t fully upwardly rotate. You can assess this with normal flexion ROM testing, with a dowel, or with a press.

- Centrated Spine (lack of rib flare)

- Full Scapular Upward Rotation (55-60°).

- Level Hands in Full Flexion

Intervention

After your assessment you will have a better idea of what your patient needs. Their needs and movement patterns displayed in the assessment will dictate where to start.

My progression usually starts with the anterior core integration, then goes to unloaded overhead, then to loaded overhead. I know this is vague, but its more about making sure you aren’t missing a step in the process. Going to a loaded press without assuring correct unloaded movement patterns or anterior core stability is a dangerous way to treat.

Compensations / Substitutions

Before you start pressing away, it’s important to know what common compensations occur with overhead shoulder movement. Here is a list of the most common strategies I see (this is not conclusive, some people find amazing ways to compensate).

- Rib Flare

- Lumber Hyperextension

- Cervical Protusion

- Inadequate Upward Rotation

- Elbow Flexion

- Scapular Protraction/Anterior Tilt

- Trunk Lateral Shift

Cues

It is important to have the right cues to prevent compensations. Each individual will require a different cue depending on their movement patterns and potential compensations/substitutions.

Eric Cressey uses 4 Different Cues depending on the athlete:

1) For Lumbar Hyperextension / Lordosis / Rib Flare = cues to engage antere core and keep ribs down

2)For Kyphotic “Desk Jockeys” = cues to keep chest up (posteriorly rotate rib cage, not lumbar extension)

3) For Depressed Sloping Shoulder Blades = cues to shrug as arms go overhead (not before) to get full upward rotation

4) For Upper Trap Dominant = cue posterior tilt of the scapula

The Exercises

Basic Anterior Core Integration

I always find it advantageous to start with some basic anterior core integration. Many people have difficulty with this concept. If you skip this step and start training scapular upward rotation on a weak/inhibited core you will only be setting them up for failure in the future. Without the core, the shoulder has to do twice as much work.

The reachback / pullover exercise is a great place to start. If the patient has difficulty getting their ribs down, you may need to regress the exercise a simple breathing drill (full exhale helps achieve “down” position and engages core).

On the other side of the difficulty continuum, the standing anti-extension exercise is a great way to integrate the core with shoulder flexion. I find this exercise very challenging when done correctly.

Unloaded Overhead Training

After you integrate the core it’s time to start training overhead. But before you load it up you want to make sure your movement patterns are clean. Start “greasing the groove” without resistance or load first. These are also great warm-ups for advanced patients.

• Unloaded PNF D2 Patterns (supine, half/tall-kneeling, quadruped, standing)

• Back-to-Wall Shoulder Flexion

• Bilateral Shoulder Flexion in Deep Squat

3 Loaded Overhead Training Progressions

- 1. Static Load in Full Flexion

Often times when people have difficulty squatting or deadlifting we start from the bottom and/or shorten the range (i.e. box squats, FMS corrective squat, rack pulls). We can apply the same logic to the same with the press. We can start from the top and shorten the range.

The top down press (Rack Press) is essentially working from the full overhead position and progressing your way down. This allows the patient to reap the benefits of the overhead position without going through the provocative motions to get there. Remember from Part I, this loaded full overhead position is where you reap all of the benefits (core, scapula, t-spine, RTC, etc.).

The emphasis for the rack press should be the static loaded hold in full flexion. I usually have my patients hold this position for at least 3 breaths per repetition. The more time in this position, the better.

Other exercises include:

Bottoms-Up Kettlebell Overhead Hold / Farmers Walk

Reactive Neuromuscular Training (RNT) with Lower Extremity (the possibilities are endless)

- 2. Progressive Angles

Another great way to progress loaded overhead training is with progressive angles. I learned this one from Eric Cressey. Starting with angled presses/pulls decreases the provocative positions while allowing for overhead adaptation.

Landmine Press (Angled Press)

Resisted PNF D2 Flexion

1/4 Turkish Get-Up (to elbow)

- 3. Full Range Overhead Training

Once your patient is able to handle all the exercises above it is safe to progress to full overhead training. From this point it is more about the SAID principle and maintaining clean movement.

Yoga Push-Up (at 2:10 in this video)

Full Turkish Get-Ups

Resisted Y’s (TRX Y’s)

Barbell Overhead Press (OHP)

Pull-Ups (eccentric → concentric)

Bottom Line

Sometimes just mentioning overhead shoulder work makes people cringe and grab their shoulders. It is often avoided in rehab and is performed/progressed incorrectly in performance training.

Everyone should be able to get their arm overhead. This position is incredible for the human body. With this article series you should be able to better assess and prescribe exercises for overhead shoulder work.

Dig Deeper

Eric Cressey – Upward Rotation in Athletes – Why You Struggle to Train Overhead & What to Do About it

Ludewig PM, Cook TM. Alterations in shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in people with symptoms of shoulder impingement. Phys Ther 2000;80:276-91

Johnson G, Bogduk N, Nowitke A. Anatomy and actions of the trapezius muscles. Clinical Biomechanics. 1994;9:44-50.

Struyf F, Nijs J, Meeus M, Roussel NA, Mottram S. Does Scapular Positioning Predict Shoulder Pain in Recreational Overhead Athletes? Int J Sports Med. 2013 Jul 3;

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.

[…] The New Overhead Concept (Part II) […]

Hi,

How would you treat someone with a very flat thoracic spine ? I do have one and wonder what exercises I could do to make it more curved because the scapula – especially the upper extremities – are not stable when overhead pressing…

It’s always difficult to give an exercise prescription without a full assessment. I would need to determine whether it is a true thoracic spine limitation, a myofascial limitation (lats), or a motor control dysfunction. Because your flat spine may or may not be the cause of your instability.

A shotgun approach would include PRI flexion exercises, lat stretches, anterior core stability, and scapula stability. Full exhale to achieve a ZOA would be of paramount importance for someone with a restricted/flat t-spine.

This is one of my favorite exercises for flexion based lat stretch: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rwN5u_psGIc

I can achieve thoracic spine flexion with no problem and thoracic spine extension to a great degree. But when I’m standing straight I have a very flat upper spine.

Naturally, I had scapular winging and fixed it by strengthening the S.A. – but I still can see the upper extremities of the medial border of my scapula protruding a little because of the flatness of my upper spine.

When I pressed overhead, I noticed that my thoracic spine went even further in extension which leaved no surface for the upper scapula to lie on (this is what I meant by “not stable”).

What are the PRI flexion exercises you would recommand ?

Thank you very much for your time; it is not easy to find information about my issue and its treatment.

The exercise above for deep squat flexion based lat stretch mentioned above is a PRI exercise. If your thoracic spine is going into too much extension during overhead movements then you should consider anterior core motor control and poor breathing mechanics as a possible culprit.

If this approach does not provide you the results you are looking for, you should seek out help from a professional.