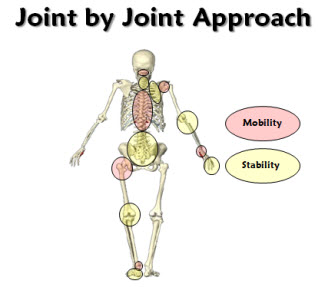

In the past 10-20 years there has been a trend towards stabilizing the proximal joint. Everything seems to be going more and more proximally. And this is a good thing! It is providing us with better outcomes and quicker pain free rehabilitation.

If you look at the knee joint you can see the progress. We’ve gone from isolated patella mobs and VMO strengthening to hip strengthening. And now we are going even further up the chain and looking at lumbo-pelvic complex.

The same thing is happening with the shoulder. We’ve gone from isolated thera band ER/IR to scapula stabiliztion. And now we are going even further and looking at the thoracic spine and ribs.

And if we go just 1 step further at both joints we end up where it all began in the first place…the core.

The Greats Love Proximal Stability

This is no where close to being a new concept. Many of our professions greatest clinicians have been emphasizing the influence of proximal stability on the distal extremities for years.

Shirly Sahrman always discussed relative flexibility/adjacent stiffness, PRI’s focus is achieving a Zone of Apposition (ZOA), PNF (Kabat & Knott) has always advocated Proximal Stability before Distal Mobility, Gray Cook prioritizes Symmetrical Core Stability, Stuart McGill discusses Super Stiffness, DNS (Kolar) starts with a Centrated Spine for a Punctum Fixum, Kelly Starrett talks about Midline Stabilization, and Janda’s Upper/Lower Crossed could be argued to be the result of poor core stability.

Anyone that uses these approaches knows of the benefits of core stability for extremity function.

It’s becoming more and more common in clinics, training rooms, and gyms. But it goes beyond empirical cases; the research on the influence of the core on the extremities seems to be increasing as well.

I would bet that in several years, core training and integration for extremity dysfunction will be as common as hip strengthening for dynamic valgus.

The Core

We could sit here for days and argue over semantics on the definition of the core. We can then spend another couple hours arguing about how it can be separated: inner core, outer core, local muscles, global muscles, anterior, posterior, lateral, etc.

This is great and can provide for some interesting discussion, but these semantics don’t change how the core works.

I try to keep it simple and define the core is the center of the body. It’s your axial skeleton and all the muscles that connect to it.

Regardless of your definition, the focus should be on how the core works, how to assess it, and how to train it for each individual patient.

Anterior or Posterior? Inner or Outter? I’m not sure how you would define this type of core stability (Quidam by Cirque du Soleil)

The Developmental Perspective

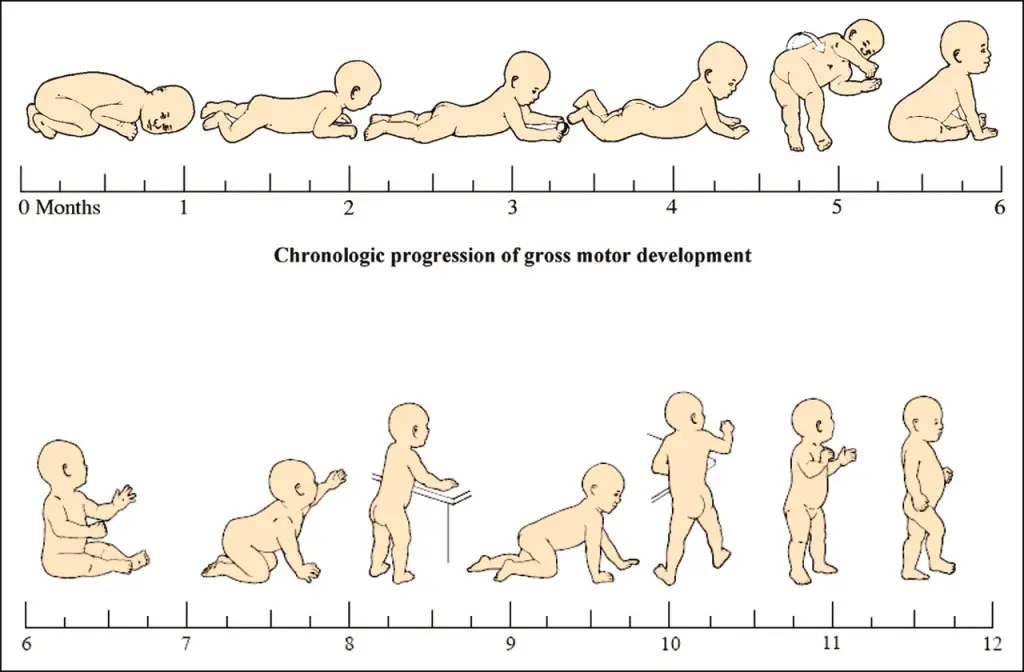

Looking at movement through the neuro-developmental lens gives us an unbiased perspective of how we ALL started to move. Every generation has developed motor functions through the same neuro-developmental kinesiology. It’s a pre-written genetic code with more than 6 million years of evolution. We are all born with full mobility; and then we struggle our way from rolling, to sitting, to crawling, to walking.

We develop our first movement patterns with minimal influence of external factors. It’s the purest form of movement that we have in this world.

It’s before shoes deprive our sensory input and lock up our ankles. It’s before we’re forced into chairs and give away all sorts of proximal mobility. It’s before someone tries to coach or teach us how to move. It’s before we can be influenced by a certain model of movement (yoga, pilates, martial arts, powerlifting, sports, etc.).

The developmental perspective shows us how humans move before the detrimental influence of their culture.

Needless to say, it’s a good standard to measure against.

How the Core Works

Developmentally, all movement starts at our core. We start to control our head, we start to gain sagittal spinal stability, and then we start moving our extremities. This combination of spinal stability in concert with extremity movement then drives the rest of the movement development. Once we have this extremity motion integrated, we start rotating and rolling, then we sit up, then we go from creeping to crawling to cruising to walking.

This is all basically a core motor control and strengthening progression. The core stability demands increase with the each progression of the developmental milestones (least=supine/prone, most=standing/walking). It’s the first SAID principle our bodies have to deal with.

If the core doesn’t fire efficiently, the baby won’t be able to perform the task and the baby will fall down. Without an integrated core, the baby won’t be able to use their extremities for manipulation and movement.

In this manner, developmental kinesiology prevents humans from progressing to the next milestone without mastering the previous one. It’s natures perfect self-limiting exercise.

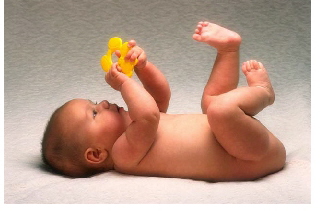

A baby doing 3 sets of 10 of the dying bug exercise…I mean, exploring movement to develop core motor control

Babies don’t perform planks, do 3 sets of 10 crunches, or isolate their transverse abdominis. Thats not how the core works. The core works to create efficient proximal stability for the production, control, and transfer of force. The core works to create a stable base for goal oriented movement. It’s a complex, integrated system of feed-forward and feed-back strategy. And it is developed through the use of the extremities.

It’s important to note that this “efficiency” is not a measure of strength. It’s an assessment of the neuromuscular patterns.

Core efficiency involves the complex coordination, timing, and motor control of ALL the muscles involved in the specific task. From the big toe on the ground to the opposite shoulder, all muscles must be fire in concert with the core. It’s not just “pre-activating” your inner core.

So what happens if your core isn’t stable? If you’re not able to transfer force and stabilize your center of gravity? If you’re not able to centrate your center?

What Happens When the Core Doesn’t Stabilize

What happens is that the next joint down has to do extra work to stabilize. The next joint down can’t transfer (unload) force to the proximal core. The next joint down ends up taking on a lot more force. The next joint down overworks to make up for the lack of efficient proximal stability. The next joint down gets locks down in attempt to “stabilize” and becomes “tight”. The next joint down becomes inefficient.

This is an example of how not having proximal stability leads to decreased distal mobility.

So that hip might be restricted and feel tight because it can’t transfer (unload) forces proximally because of a lack of core stability. And those ankles might always be locked up because they might be constantly active as a postural balance strategy because of a lack of core stability (unstable center of mass=instability=terminal segment compensation).

That’s not to say it can’t swing the other way. With a lack of proximal stability, the distal segment will not be as efficient at producing force/torque.

So that overhead shoulder might feel weak because it can’t receive valuable proximal force production from the core. And those achilles might be overworked because they’re trying to make up for the lack of proximal stability from the hips and core.

Assessment & Intervention

Assessment

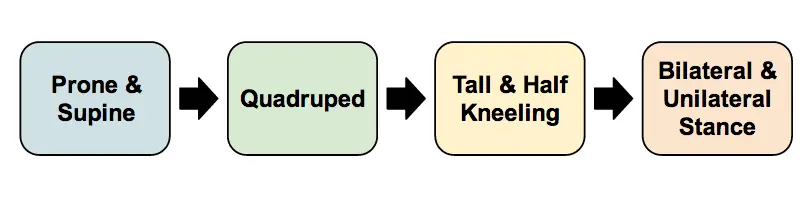

I assess the core using a developmental postural stability progression. This progression is essentially going from lying on the ground to standing. From a stable base to a narrow base. From minimal degrees of freedom to maximal degrees of freedom (joints available).

Postural Assessment

Each posture is progressed from wide base of support to a narrow base of support.

- Supine/prone is assessed with either rolling patterns or foam roll marching (depending on client and space).

- Quadruped is assessed with Alternate UE & LE (“bird-dog”).

- Tall & Half Kneeling is assessed with half kneeling to ensure that there are no asymmetries.

- Single leg stance is assessed with eyes open and eyes closed.

I usually assess people for 10-20 seconds in each posture. I look for the movement quality, common pattern dysfunction, and compensatory strategies. The goal is for the patient to stabilize the closed chain extremities through their core. I don’t get too caught up in the positioning of the open chain extremities.

Intervention

My intervention follows the developmental postural stability progression in a static to dynamic fashion (low threshold to high threshold).

After I have their core movement assessed, I use these positions at their “Edge of their Ability” to develop reflexive static stability and core efficiency. I usually tell my patients to “find the point where they struggle, but don’t fail”.

Once they can demonstrate the most difficult level of static stability (narrow base), I add either upper extremity or lower extremity dynamic movements in these postures. From here, the possibilities are limited by your creativity.

Some Examples:

• Upper Extremity: Wall Slides in Tall Kneeling, Plank with Reach, Quadruped T’s, UE PNF Patterns in Developmental Postures

• Lower Extremity: Side-Plank with Hip Abd/Flex, Bridges with Marching, Plank with Hip Extension

• Both: Chops & Lifts, Single Leg Asymmetrical Deadlift, Resisted Quadruped Alt UE/LE, Turkish Get-Up, Quadruped Rocking, Crawling/BearCrawling

Bottom Line

- “Any purposeful movement first requires spinal stabilization” -Pavel Kolar

I try to add some core integration for all of my patients. It’s easy to do, there are tons of benefits, and the patients usually like it. Plus, it taps into the hard-wired CNS developmental patterns.

You can incorporate this tomorrow. Just keep doing what you’ve been doing with your patient, but throw them at the edge of stability in one of the developmental postures. They’ll get more sensory input, and therefore a better motor output. Their core gets integrated, and you have a new trick up your sleeve. Everyone wins.

Even if you don’t buy into this whole proximal stability thing, you should at least consider it when that ankle dorsiflexion hasn’t improved in 6 weeks.

Dig Deeper

Gray Cook:

Motor Control, Stability, and Prime Movers

Kelly Starrett – Midline Stabilization, Example of Midline Stabilization Fault

Seth Oberst – Motor Control Priority

Steve Smith – DNS

Lieberman, Daniel. The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, and Disease. New York: Pantheon, 2013. Print

Walter, Chip. Last Ape Standing: The Seven-million Year Story of How and Why We Survived. New York: Walker &, 2013. Print.

Cook, Gray. Movement: Functional Movement Systems: Screening, Assessment, and Corrective Strategies. Aptos, CA: On Target Publications, 2010. Print.

Liebenson, Craig. Rehabilitation of the Spine: A Practitioner’s Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007. Print.

Studies:

Moreside JM, et al. Hip joint range of motion improvements using three different interventions. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 May;26(5):1265-73.

Leetun DT, et al. Core stability measures as risk factors for lower extremity injury in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004 Jun;36(6):926-34.

Kibler WB, Press J, Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Med. 2006;36(3):189-98.

Wilson JD, et al. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005; Sept13(5):316-325

Shinkle J, et al. Effect of core strength on the measure of power in the extremities. J Strength Cond Res. 2012 Feb;26(2):373-80

Granacher U, et al. The importance of trunk muscle strength for balance, functional performance, and fall prevention in seniors: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2013 Jul;43(7):627-41.

Gottschall JS, Mills J, Hastings B. Integration core exercises elicit greater muscle activation than isolation exercises. J Strength Cond Res. 2013 Mar;27(3):590-6.

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.