Low back pain is one of the most common injuries we see. Traditionally you always hear a lot of information regarding excessive lumbar flexion. And with the amount of information readily available in our society, many patients already know this as well. This has caused some therapists and patients to walk around terrified that the next time they bend over their L5-S1 disc will splatter against the wall behind them. But what about the other direction? What about the potential problems in extension patterns?

We’ve concerned ourselves so much about “blowing out a disc” with flexion that we’ve completely overlooked extension problems.

Over Extension

Maybe it’s because I practice in NYC where people are constantly on the move and always going 1,000 miles per hour. Maybe it’s because our society is spending more time sitting down and plugged in. Maybe this excessive stress leads to a state of inhalation (PRI concept) which would increase lumbar extension. Maybe it’s our footwear. But whatever the reason, I’m seeing ALOT more patients with a lumbar extension dysfunction.

When it Happens?

Most of the time the lumbar extension error doesn’t present itself until you get the patient moving. This is something subtle that they are repeatedly doing throughout the day as they move. It’s a micro-trauma that accumulates until they shoot over their pain threshold.

You may be able to guess that it will be a problem when you assess their posture and see that you rest a glass of water on their sacrum because they’re so anterior tilted. But most of the time it won’t come out until you look at their movement patterns and challenge them with loads.

Why it Happens?

Like all kinds of movement dysfunction, this extension fault is different for every individual. To say conclusively that it happens for one particular reason would be overlooking the complexity of the individual. A full assessment will give you a better picture of what’s going on.

Even if you don’t know the exact reason, focusing on movement will allow you to correct the dysfunction without having to know the exact structural culprit. And if you can correct the dysfunctional movement, then who cares what the exact pathoanatomical cause was? Pathomechanics always trumps pathoanatomy in our field.

So how do you explain the pathomechanics? This dysfunction is easy to understand if you have a mobility restriction, but what if their SFMA is fairly clean and the breakouts all lead to stability/motor control dysfunction (no mobility impairments)?

Since it often only presents itself with movement and load, it is a compensatory mechanism to stabilize. Why go into extension? Because the muscles don’t have to work as hard in this position. The closed packed position of joints is a stable position. The body can rely on static osseous stability instead of dynamic myofascial stability.

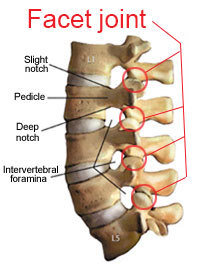

So what’s happening is that these patients are relying on their lumbar facets for stability. Instead of creating efficient core stability and transferring torque from their hips, they just compress and hang out on their facet joints. Doing this over and over throughout the day and with load in the gym would make anyone’s back hurt.

Assessment

As mentioned above, you may see an excessive anterior pelvic tilt (hyperlordosis) and the patient may complain of pain with extension activities. This is a good start to your hypothesis, but you need to prove that they have a dysfunctional compensatory movement pattern before you blindly attack it. I find the best assessment system for movement patterns to be the SFMA.

9 times out of 10 someone with this dysfunction will fail the multi-segmental extension pattern. When you break it out and find it’s not a mobility issue, then you can rest assure that they probably have an extension stability/motor control problem. This directs you towards rolling and a developmental stability assessment.

Another key to this assessment is seeing how they move with the hip hinge. This tests their ability to stabilize their spine and create torque from their hips. If they can’t control their lumbar spine and hips then they will hyperextend onto their facet joints for stability. And this usually reproduces their pain.

The video below shows a patient who has an extension stability/motor control dysfunction. She is hypermobile and has no mobility restrictions.

How to Fix It

If you’re lucky and it’s a mobility problem you will be able to resolve their restrictions and easily train the movement pattern back to normal.

However, if it isn’t a mobility problem then it isn’t going to be an easy fix. You can’t just give them planks and dying bugs and expect the movement pattern to resolve. While working on their anterior core and breathing will help, you will have to do one of the more difficult things in our profession…coach them out of it. You have to fix their movement pattern.

Torque & the 1-Joint Rule

Kelly Starrett often talks about creating torque and the one-joint rule in his book “Supple Leopard“. These are great concepts you can use to assess and treat movement dysfunction.

Our body moves (and stabilizes) from the torque that muscles create on our bones. So it makes sense that some patients will benefit from verbal cues and education on how to create it.

Kelly describes the one-joint rule as the general principle that “you should see flexion and extension movement happen only at the hips and shoulders, not your spine.” This of course doesn’t mean that your spine shouldn’t move, it just means that during high-load or high-velocity tasks your 2 ball & socket joints (hips/shoulders) should be moving while your spine stabilizes to transfer the forces.

Using these rules as a blue-print to teach patients to stabilize their spine and create torque through their extremities can pull them out of the gumby like stability problem. In the video below, Kelly takes someone from an extension dysfunction to a normal movement pattern simply by using verbal cues.

Bottom Line

We traditionally concern ourselves (and our patients) about the dangers of lumbar flexion. However, any excessive and misused movement is dangerous. Lumbar extension is no different and is a common problem in many low back pain patients.

This post also provides an example of how I have integrated Kelly Starrett’s work with Gray Cook’s SFMA approach.

Sometimes clinicians can limit themselves by following only one system religiously. By doing so you can miss out on some great aspects of other approaches. I’ll admit that I am biased towards the SFMA, but that doesn’t prevent me from using other systems as well. In fact I’ve found that adding other approaches in to your practice benefits you as a clinician, and more importantly it benefits your patient.

Bruce Lee said it best: “Absorb what is useful, discard what is not, add what is uniquely your own.”

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.

Thanks for this post. SFMA is a gem and the subject of this blog post is part of the answer I was looking for.