I am a big fan of the FMS (Functional Movement Screen) and SFMA (Selective Functional Movement Assessment). Together these screens and their associated principles make up the Functional Movement Systems.

I’ve been using this system for a couple years and have had a lot of success with it. The more efficient I become at this approach, the more my outcomes improve.

I still have much to learn and am by no means an expert, but I thought I’d share the 4 biggest mistakes I see people make with the Functional Movement Systems.

4 Functional Movement Systems Mistakes

1) It’s Not a Kinesiology or Biomechanics Test

The SFMA and FMS are both seven baseline movements that are used to assess how someone moves. The big point here is that this is not a kinesiological test or a biomechanical test. It’s not a strength, stability, or a mobility test. It is not a test for anything in isolation.

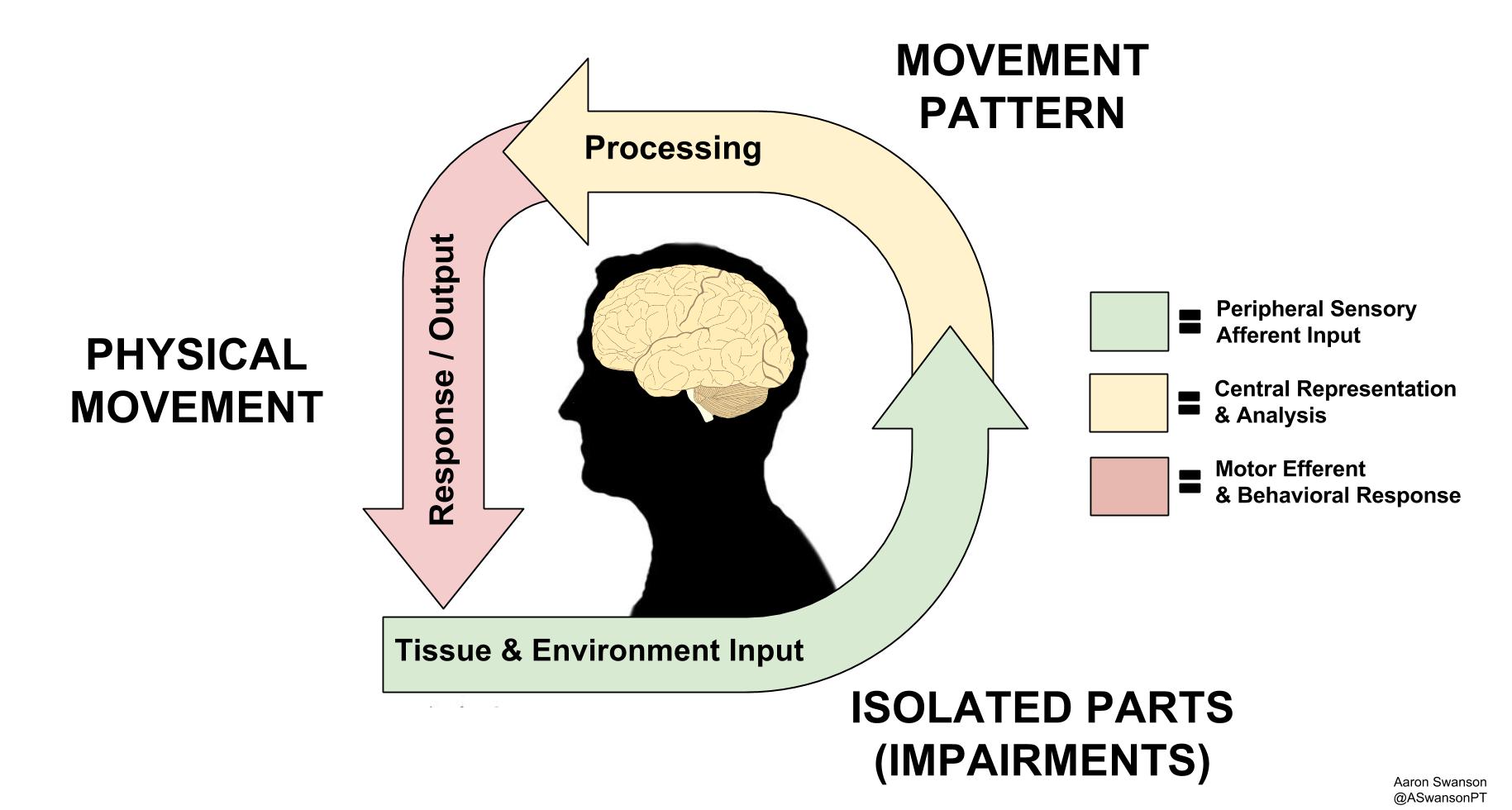

It’s a complex neuro-based movement assessment. It incorporates all the peripheral inputs coming into the CNS (mobility, muscle tension, joint ROM, position, tensegrity, vision, vestibular, etc.). It incorporates how these inputs are analyzed and processed in the CNS (movement history, expectations, motivation, ANS state, etc.). And then, it incorporates the output of this process – the physical movement we can see.

Based off of Louis Gifford’s Mature Organsim Model – How Movement Goes From Inputs to Outputs Via the CNS

Essentially, the top tier tests are screening your neuro-tag for a standard 7 movements. It shows what movement looks like in your brain. It shows how the inputs are processed into outputs. And this happens continuously in real-time throughout the entire movement.

This isn’t just a theory. It’s how human movement works.

Anytime you loosen up someone’s ankle DF (inputs), it needs to be integrated in the CNS (processing) for the specific movement pattern that was dysfunctional (outputs). Sometimes this will spontaneously happen after creating mobility, other times you need to “show” the brain the new mobility and create the new movement neuro-tag.

2) 7 General Movement Standards

One of the big complaints I hear is that “people do more than just 7 movements”. While this is a brilliant observation, it doesn’t debunk the system.

We can all understand Bernstein’s Problem (Degrees of Freedom Problem). The amount of freedom of the joints, coupled with the kinetic pulls of all the different muscles/fascia/connective tissue, basically creates an infinite amount of possible ways to move. Therefore, the nervous system has an infinite amount of motor programs to choose from.

In other words, with the plethora of variables in human movement, there cannot be just one “right” way to move.

And this is a good thing; it allows our species to have more options to choose from when trying to adapt to a specific environment or task.

The problem exists in the practitioners job of assessing the infinite. How do you go about testing the infinite ways of movement in a 45 minute eval?

This is where the SFMA/FMS comes in.

It is simply the best standard we have for efficiently screening the infinite movement patterns.

It is a funnel to find the dysfunctional movement family.

How does this apply to your patient’s specific problem?

Simply look at the variables associated with the movement screen and match it with the patients dysfucntional movement or functional complaint. You should be able to find something in common with your patients specific movement problem and one of the 7 movements (FMS or SFMA).

An example may help understand this concept.

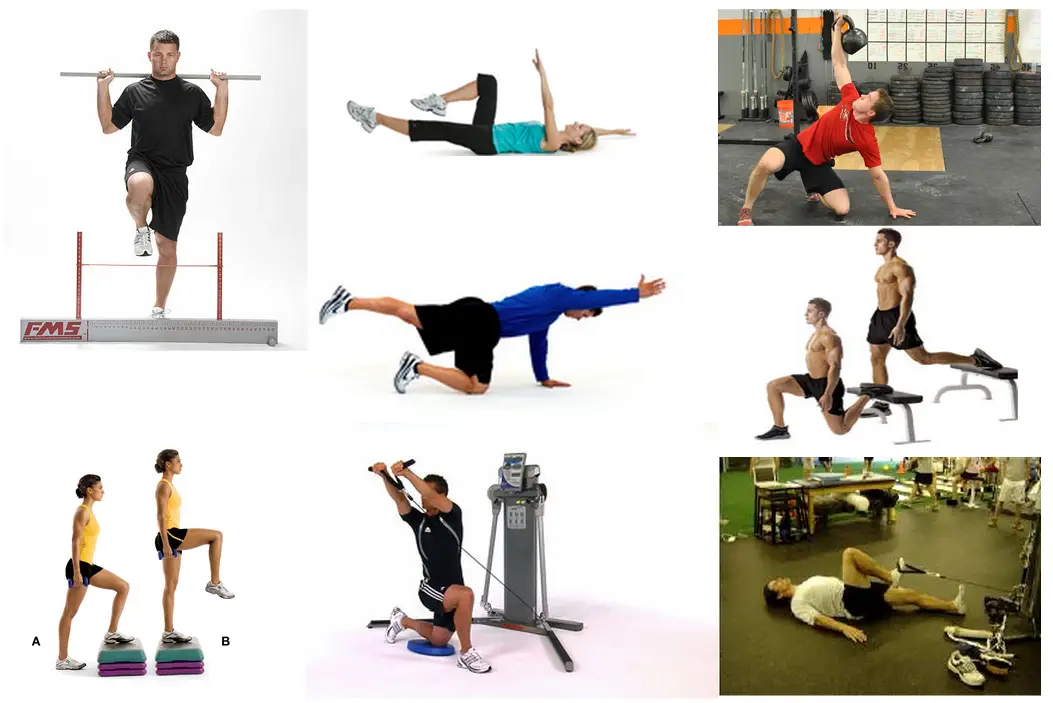

If a patient fails MSF (Multi-Segmental Flexion), it means that this individual will likely have difficulty with movements that shift their COG behind their BOS, or lengthen a their posterior chain, or involve a hip hinge, or involve lumbar flexion, or require motor control of trunk flexion, etc. (see picture below for everyday common movement patterns).

It doesn’t only mean that they can’t touch their toes and fail a test. It doesn’t mean they need to move exactly like the MSF screen every time they bend forward in their life. It just means their MSF movement pattern is dysfunctional and this will likely affect many of the other infinite movements that share the same variables.

In other words, it narrows the infinite and points you towards a family of movement patterns that need work.

The Flexion Movement Pattern Family – each one of these movements have something in common with the SFMA MSF Movement Pattern

3) It’s More Than Screening for Impairments

A common misconception about the SFMA is that it’s only used to find local impairments.

Yes, finding the local impaired segment and tissue dysfunction is important. But what’s more important is how the local impairment affects the global movement pattern.

Impairments cannot exist in a purely isolated fashion. Impairments only exist in the context of the whole human body. It’s not until the impairment adversely affects a movement (or posture) that it becomes a problem.

For example, an isolated latissimus dorsi restriction doesn’t mean anything by itself. There are plenty of people who sit at desks all day, don’t exercise, and never lift their arms overhead. Therefore, this impairment rarely becomes a problem for them. But if this same person goes out and tries to hit a tennis serve over the weekend, this becomes a serious impairment that affects their MSE (Multi-Segmental Extension) movement pattern. Compensations will occur and the risk of injury will increase.

Yes, the lat restriction is important, but it only becomes a dysfunction in the context of movement.

The goal of they system is to determine the local impairment AND the movement patterns that are most significantly affected.

A local latissimus dorsi restriction doesn’t mean much when sitting at a desk, but it becomes a big problem in the context of a tennis serve

4) It’s a Screen & Assessment, the Intervention is Wide Open

This mistake often occurs as a result of the first 3 mistakes.

Most people are able to address the local impairment, but some have difficulty integrating this new input into the movement pattern.

The movement pattern intervention is basically an application of the concepts to the individuals specific assessment. There is no cookie cutter protocol to follow. It’s open to the practitioner, the client, the environment, and the task/goal.

If you understand that it’s a complex neuro-based movement system, then you can understand there are an infinite amount of options to achieve the same result. First address the breakouts (inputs), then integrate them back into the global movement pattern (processing), and finally re-assess the movement pattern (output).

Gray Cook has discussed this process in his 3 R’s approach: Reset, Reinforce, & Reload.

Again, it helps to first think of it as a family of movements patterns. Try to create similar sensory inputs that are “relatives” of the top tier movement pattern. They don’t have to be identical twins, you just have to be able to tell that they’re related.

If the patient fails MSF, address the local impairments, then integrate them back into the movement pattern. To do this, just pick an exercise that shifts their weight back, or flexes the trunk forward, or eccentrically lengthens the posterior chain, or rounds the lumbar spine, or requires a hip hinge. Or a combination of those variables.

The same thing goes for the FMS. If the patient fails the hurdle step, work on something that stabilizes the stance leg in hip extension, or open chain hip/knee/ankle flexion, or the scissored position (hip flexion & extension), or work on something that stabilizes the trunk upright in the dysfunctional scissored position. Or a combination of those.

What you choose as your intervention should depend on the results of the movement screen, the breakouts, the examination, your patient, and your own treatment style.

If this open territory makes you uncomfortable, the System has a nice 4×4 exercise progression based on the neurodevelopmental perspective. This may be the closest thing you will find to a “protocol” for movement patterns.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what approach you use to address the findings in the screen and assessment.

There are many different ways to achieve the same thing.

As long as it simulates the similar inputs of the movement pattern, you should get a positive change. If you don’t get a positive change, the screen will tell you.

And this is may be the most valuable aspect of The System. It allows for you to “check your work”. It gives a clear indication for which interventions work, and which ones don’t.

The System allows you to methodically add and subtract interventions until you achieve the desired outcome.

It gives you efficiency and effectiveness, while taking nothing from the way you currently treat.

Hurdle Step Movement Pattern Family – Which one your patient needs depends on their movement assessment and breakouts

Bottom Line

The Functional Movement Systems is a very useful clinical tool. There is much more to this approach than simply screening 7 movements. Understanding the concepts and principles of this approach will help to prevent errors and increase efficiency and outcomes.

Disclaimer

I do not work for or have any affiliation with the FMS/SFMA System. This post does not represent the System or anyone affiliated with it. This is simply my interpretation of the system and some thoughts that will hopefully improve people’s understanding of it.

—

The main reason I do this blog is to share knowledge and to help people become better clinicians/coaches. I want our profession to grow and for our patients to have better outcomes. Regardless of your specific title (PT, Chiro, Trainer, Coach, etc.), we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement. I hope the content of this website helps you in doing so.

If you enjoyed it and found it helpful, please share it with your peers. And if you are feeling generous, please make a donation to help me run this website. Any amount you can afford is greatly appreciated.

Well put. A lot of nice points. Detractors of the FMS group will certainly find something in what you wrote to be up for debate, and their bumptious approach is more of a distraction of the points they are actually making. I linked here from Erson’s blog BTW.

Well put together and explained Aaron! Thank you!

Well written & great articles you’re pointing your post to. As a chiro it’s refreshing to see other professionals see “we all have the same goal of trying to empower people to fix their problems through movement”.